How many languages are indigenous to the Americas?

In the United States, we’ve all heard of commonly talked-about Native American tribes; the Iroquois, the Navajo, the Lakota, the Cherokee. And some of us know the local tribe whose land we live on; the Chinook, the Seminole, the Ojibwe, and so on. But did you know that a vast majority of Native languages spoken by indigenous people in North, Central and South America are not related to each other whatsoever?

Welcome to Not Trivial! A podcast that takes a deeper dive into the stories behind the trivia questions you might’ve heard at the pub. My name is Liz, and I’ve been a trivia nerd since I was young. My parents and I would play Trivial Pursuit often. Still do. I’ve hosted pub trivia, I’ve played pub trivia, and I’m a collector of random history, language, and world culture facts. One of my greatest passions is sharing what I’ve collected with others. I’m hopeful this podcast makes the trivia questions feel less trivial, and more important to understanding how the past creates the present, and subsequently the future. Let’s get started…

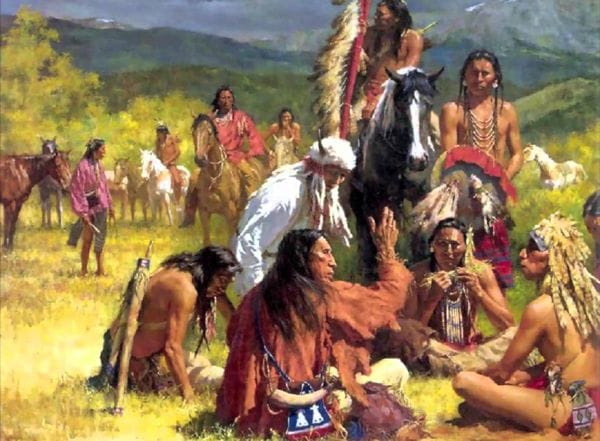

Let’s have some fun today, shall we? Hopefully, you find linguistics fun. In this last episode of the first season of Not Trivial, we start by recognizing the people who first inhabited the Americas. The peopling of the Americas began about 14,000 years ago. There are both DNA and linguistic links between populations in Siberia and the Americas. The theory that hunter-gatherers crossed a land bridge across the Bering strait does make sense. But it’s still unclear how and when and from where exactly people migrated.

There are many indigenous peoples, some who are traditionally hunter-gatherers, others who practice agriculture or aquaculture. Many societies have varying degrees of knowledge of engineering, physics, mathematics, astronomy, architecture, medicine, and metallurgy. Currently throughout the Americas, there are over 70 million indigenous people living today. Mexico is the country currently with the largest indigenous population, upwards of 20 million. The United States has just under 10 million. Guatemala, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Canada, Brazil, and Ecuador round out the top ten countries with significant indigenous populations. Several of these countries recognize indigenous languages as one of their official languages, as well.

Guarani has a speaking population of roughly 6.5 million and is an official language in Paraguay and Bolivia. Southern Quechua has a speaking population of roughly 5 million and is an official language in Bolivia and Peru. We’ll take a look at some of these languages with a strong modern sense of identity and culture. But we’ll also look at other languages that have far fewer living speakers and are classified as Endangered. Like Blackfoot, spoken by only about 30,000 people, classified as Definitely Endangered. Or Aleut, spoken by fewer than 100 people, classified as Critically Endangered. There are so many indigenous languages in the Americas, we won’t be able to dig deep into all of them. But we’re definitely going to get nerdy today, and pay our respects to languages that have evolved over thousands of years.

We start our journey in North America, where there are approximately 300 spoken (or formerly spoken) indigenous languages. There are 29 different language families. The three largest families, comprising the most distinct languages, are the Na-Dene, the Algic, and the Uto-Aztecan families. The Na-Dene family consists of Tlingit, Eyak, and Athabaskan languages. Tlingit, a Critically Endangered language, is centered in Southeast Alaska and Western Canada. Tlingit was initially translated into Russian using the Cyrillic script, by Orthodox church missionaries, at a time when the Russian Empire expanded not only into Alaska, but all the way down the Pacific coast into northern California. When the US purchased Alaska in the 1860s, English-speaking missionaries began their own translations of Tlingit using the Latin script.

Tlingit is notable for its complex phonological system. Just to provide a brief overview of phonology, there are various sounds broken up into categories: alveolar (sounds that use the tongue up against the back of the teeth, like the English letter ‘t’), velar (sounds that use the back of the tongue against the soft palate of the mouth, like the English letter ‘k’), uvular (sounds that use the back of the tongue against the uvula, like the English letter ‘g’), and labial (sounds that use the lips rather than the tongue, like the English letter ‘b’). There are two other sound categories, glottal and palato-alveolar, for sounds like the English letter ‘h’ and the English letter ‘j’, respectively. To get back to Tlingit and its phonology, it has no labial sounds other than the sound ‘m’. This sound in particular is used in almost 95% of all spoken languages, so it’s not surprising Tlingit uses it. However, there is no sound for ‘p’, ‘b’, ‘f’, or ‘v’ in Tlingit. And they have sounds that Indo-European languages do not, called ejectives. Ejectives are consonants that are voiceless but pronounced with a glottalic egressive push of air. So instead of the simple velar ‘k’ sound, you add what sounds like a glottal stop as well: [k’].

Ejectives are used in roughly 20% of spoken languages worldwide. They can be found in other indigenous language families of the Americas, including Athabaskan, Siouan, Salishan, Mayan, Aymaran, Quechuan, and Chonan. The Athabaskan languages are 43 spoken languages strong. They range from Koyukon in the northern parts of Alaska to Chipewan in the north-central parts of Canada. From parts of the Pacific Coast in Oregon and northern California, as well as the southwest deserts of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. How and why these languages of the same family are spread out over such a vast geographic area is unknown. And there’s a significant gap of land between northern Athabaskan languages in north Canada and southern Athabaskan languages in New Mexico. And it’s not a language desert in between either - it’s actually inhabited by many of the Uto-Aztecan languages, a completely different family.

One of the most well-known Athabaskan languages spoken today is Navajo. There are over 170k speakers of Navajo, but it is still considered a Vulnerable language, which does make it Endangered. Navajo as a language has very few loanwords, or words taken from other languages. This is due to its development isolated from other languages, but also its complex morphology. Can you guess what’s coming next? A brief interlude on morphology: it’s quite simply the study of words. But more specifically, how words are formed and their relationship to other words in the same language. For example, studying the roots of words, prefixes, parts of speech, even intonation. In English, the famous “buffalo” sentence is a great exercise in morphology. In Navajo, nouns are not needed to complete a sentence. It’s actually the verbs that carry the bulk of information when speaking. This is true for many indigenous languages actually. The Navajo language relies heavily on affixes, but are not used in typical prefix or suffix ways. Verbs contain more meaningful units of speech than nouns through the use of affixes. Verbs don’t adhere to tenses necessarily, but there are inherent aspects to a verb. An aspect expresses how an action or event extends over time. An example in English would be the difference between “I helped him” and “I was helping him”. You can imagine “I helped him” being continuous over time in the past. Versus “I was helping him” expresses an act that has ended. In Navajo, there are 12 aspects available to a verb. There are also 7 modes a verb can be conjugated by, including imperfective, perfective, progressive, iterative, usitative, future and optative. The imperfective is for incomplete activities, the perfective is in the past and future tenses only for completed tasks. The progressive is for actions that are ongoing, the iterative for events that are repeated. The future is self-explanatory, it happens in the future only. Usitative mode is for actions that happen customarily but not always. The optative mode is for potential actions the speaker wishes for.

Let’s get some examples, so you don’t fall asleep. The English verb “to play” in Navajo can be seen in its various verb forms as follows: first person singular imperfective (“I am playing”) is naashné, first person plural imperfective (“we are playing”) is neiiʼné. The suffix of -né expresses the imperfective mode of the verb. The affix after the starting syllable expresses singular vs plural (“-sh” vs “-ii”). Like other languages, there is the first person (“I” or “we”), the second person (“you”), the third person (“he/she/it/they”), and Navajo uses the fourth person as well. For an English speaker, it is likened to saying “one is playing”. Navajo is a very verb-heavy language, as we’re learning. And verbs have further classifications than the ones we’ve covered so far. A verb can express motion as well. As in, “Is the object in motion due to continuous physical contact?” because you are handling the object, like the verbs “carry” or “bring” or “lower”. There is also “Is the object in motion due to being propelled?”, like the verbs “throw” or “drop”. And there is “Is the object in motion due to free flight?”, like the verbs “fly” or “fall”. Verbs can also include what are called handles, simply based on the shape of an object. Handles are affixes like -ą́ specifically for solid round objects, like apples or coins, versus -jaaʼ specifically for a plural of small objects like seeds. There are a further 8 shape classifications that can be used as handles in verbs.

And we’re just brushing the surface on how deeply complex and beautifully succinct Navajo is as a language. As I said before, the Athabaskan languages are separated geographically north vs south. And in between are some of the Uto-Aztecan languages, like Northern Paiute, Shoshone, Hopi, and Comanche. These languages are spoken in modern-day states like Nevada, Utah, and Arizona. Down the western edge of modern-day Mexico, excluding the Baja peninsula, are about 6 or 7 language groups, like Opata, Yaqui, Mayo, and O’Odham. The most southerly Uto-Aztecan language spoken in Mexico is Nahuatl. This was the language of the Aztec or Mexica people. The ancient city of Tenochtitlan is the most famous of this culture. And many modern English words loaned from Mexico are actually Nahuatl words. Like, avocado, coyote, chili, chocolate, tomato, and axolotl. One of the markers of Nahuatl, among many, is its use of reduplication. This is when the first syllable of a root word forms a new word entirely. When used in nouns, it will pluralize the noun. But it can also form a diminutive or a derivation as well. When used in verbs, it will express a repetitive action. For example: /wetsi/ 'he/she falls' or /we:-wetsi/ 'he/she falls several times'. Nahuatl also uses glottal stops in a specific manner. They’re called saltillo. Remember the glottal stop from Tlingit to create ejective sounds? In Nahuatl, the glottal stop is not an ejective, but a full phoneme (or sound) in its own right. To carry on the example from /wetsi/ and create the third person plural, the verb becomes /weʔ-wetsi-ʔ/ 'they fall (many people)'.

We are blessed to have literature and significant amounts of written language in Nahuatl, which does make it unique among indigenous American languages. Nahuatl literature encompasses a diverse array of genres and styles, the documents themselves composed under many different circumstances. Pre-conquest Nahuatl had a distinction between tlahtolli 'speech' and second cuicatl 'song', akin to the distinction between "prose" and "poetry". One of the most important works of prose written in Nahuatl is the twelve-volume compilation generally known as the Florentine Codex. Its volumes cover a diverse range of topics: Aztec history, material culture, social organization, religious and ceremonial life, rhetorical style and metaphors. The twelfth volume provides an indigenous perspective on the conquest. Aztec poetry makes rich use of metaphoric imagery and themes and lamentations of the brevity of human existence, the celebration of valiant warriors who die in battle, and the appreciation of the beauty of life.

It’s true that indigenous languages and peoples were eventually decimated through interactions with colonial powers, like the Spanish, French, or English. But it is also these early interactions that can provide priceless historical accounts of cross-cultural learnings. Some of them are violent incidents, others less violent. Indigenous North American language families, like Iroquoian, Siouan, and Algonquian, have made their mark on the colonial powers who stepped foot in their territory. Iroquoian languages are ones like Mohawk, Huron, and Cherokee. The Mohawk people were part of the Iroquois Confederacy, or Haudenosaunee. They lived on the eastern edge of the Confederacy’s area and were the gatekeepers for any invasions from the east. The Mohawk call themselves Kanienʼkehá꞉ka, or “people of the flint”, because they became wealthy through trade of flint. They had a history of raiding and conquering other tribes in the region, neighbors like Algonquin-speaking Mohicans. In 1609, when a band of Hurons led Samuel de Champlain and his crew into Mohawk country, an impromptu skirmish unfolded. Both sides were shocked by the presence of the other. Champlain and other Frenchmen were astounded by how the Mohawk dressed and carried themselves. The Mohawk had never seen metal helmets and body armor before. Champlain and his men, in that skirmish, killed three Mohawk chiefs, and the Mohawk retreated due to their lack of knowledge in fighting such a foe. This one moment sparked the Beaver Wars. You can look that one up on Wikipedia.

For the Cherokee, the first known European contact was with the Spanish. Hernando de Soto was leading an expedition in May of 1540. Since they were on a mission that kept them on a march, the Cherokee saw them as simply passing through various villages in their land. Like other peoples, the Cherokee were victims of new infectious diseases the Spanish brought with them. Many villages were impacted and many people died. The Cherokee defended their lands against the Spanish initially. The Spanish had thought of trying to conquer and settle the lands, but could not withstand the fight on lands that were so far from the coast. This is in southern Appalachia, so the Cherokee were well-able to defend their lands due to the geography of the land itself. They were a powerful tribe and were seen by Europeans as excellent to trade with, but be cautious to keep on their good side, as they were also known as fierce warriors.

The Sioux people of Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa, and Nebraska, are distinguished by speaking two branches of the same language: Lakota and Dakota. The Sioux were actually pushed west of the Great Lakes by Iroquoian tribes. The Lakota people are where the stereotypical image and language of the “American Indian” come from. Sitting Bull wore his hair in two braids and had earned the honor of wearing eagle feathers. He was a holy man and tribal warrior. Lakota greeting phrases like “Háu kȟolá” were simplified to anglicized words like “How!”. Ironically, the word “Háu” in Lakota is the only word in the language to use a dipthong, which means it may have been loaned from a different indigenous language altogether. The Kevin Costner movie “Dances with Wolves” from 1990 was a screenplay written heavily in Lakota, since the main character assimilates into Siouan culture. However, reception from indigenous people was mixed. There were some who praised the movie for highlighting Siouan culture and language in a different way than previous Westerns from Hollywood. Others criticized the authenticity of the Lakota language used in the film. A Blackfeet filmmaker said: "I want to say, 'how nice',... But no matter how sensitive and wonderful this movie is, you have to ask who's telling the story. It's certainly not an Indian."

One interesting linguistic fact of Lakota is that it uses postpositions. As opposed to prepositions, like “at” or “in” or “around”. In Lakota, the postpositions él and ektá are synonyms of each other, but are used in different occasions. Semantically, they are used as locational and directional tools. What are semantics? Great question! Semantics is the part of linguistics concerned with meaning. In the case of the two postpositions in Lakota, a pointer for when to use él and when to use ektá can be determined by the concepts of location or motion; and space vs. time. For example:

- space / rest: "in the house" [thípi kiŋ él] (This sentence is only describing location of an object, no movement indicated)

- space / motion: "to the house” [thípi kiŋ ektá] (This sentence is referring to movement of a subject, it is directional in nature)

- time / rest: "in the winter" [waníyetu kiŋ él] (This sentence refers to a static moment in time, which happens to be during winter)

- time / motion: "in/towards the winter" [waníyetu kiŋ ektá] (This sentence is delegated to time, but time which is soon to change to another season)

Lakota also uses demonstratives, which distinguish the distance from the speaker. There are nine demonstratives, establishing being near to the speaker, near to the listener, away from both speaker or listener - these are expressed in the singular, dual, and plural. One person vs two people vs multiple people.

The North American language family that probably takes up the largest geographical area is Algonquin. Languages in this family are Cree, Ojibwe, Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Shawnee, Miami Illinois, Menomini, Fox, Potawatomi, Mi’kmaq, Abenaki, Mohican, Delaware, Powhatan, Massachusett, and several others in smaller regions of the Northeast. These languages are all considered polysynthetic, meaning they contain complex verb structures, which make for longer words. Long words that feel like their own sentences. Just like other indigenous languages, one word can contain multitudes. Algonquin nouns make the distinction between animate and inanimate objects. And nouns can also be contrasted between proximate and obviative. Proximate nouns are central and important to the discourse taking place, while obviative nouns are less important to the discourse taking place. Which creates even greater context to a conversation. It gets even more fun from there, because Algonquin languages also have a hierarchical morphosyntactic alignment. That was a mouthful - but long story short, it means the use of a voice where the subject of the sentence outranks the object, or an opposing voice which creates the opposite effect.

Many words still used in English today are loanwords from Algonquin languages. Such as, ‘caucus’, which could be from the Algonquin word for ‘counsel’ or the word for ‘orator’. Also, the words ‘chipmunk’, ‘hickory’, ‘moose’, ‘pecan’, ‘raccoon’, ‘skunk’, ‘toboggan’, ‘totem’, and oddly enough the word ‘eskimo’. ‘Eskimo’ was a word taken from a Cree dialect to refer to the Mi'kmaq tribe, meaning “snowshoe-netter”.

Cree is actually a dialect continuum, rather than one language. It uses a syllabary, rather than an alphabet. Each symbol represents a consonant, and can be written in four directions. The direction the symbol takes corresponds to the vowel accompanying the consonant. As with many other indigenous languages, diacritics are needed to distinguish various syllables when used grammatically. The Cree syllabary has also not traditionally used punctuation like the period. Traditionally, there was simply more space between the end of the sentence and the beginning of another. Cree is also a main component language in what are called contact languages, like Michif, which is a combination of a Cree dialect and French. Michif uses Cree verbs, question words, and demonstratives, while also using French nouns. Bungi is also a contact language, being a mix of Scots, Gaelic, Ojibwe, and Cree.

One of the most elusive indigenous languages of the Americas is the Eskaleut language family tree. Aleut, Yupik, and Inuit being languages therein. These languages are geographically in North America, but linguistically they are much more strongly related to Siberian and other Asian languages. This means they may have been the most recent of indigenous people to have crossed to the American continent. Notable features of Eskaleut languages are that they have relatively few root words, and that they use multiple voiceless phonemes, including voiceless nasals. When I say that Eskaleut has relatively few root words, I mean that there are only roughly 2000 root words for the languages to create from. However, these root words are then added to with the use of postbases. These are like suffixes. Sort of. This explains the stereotypical comment about these languages having many words for ‘snow’. It’s not that they have multiple words for ‘snow’, but that they utilize root words alongside postbases to expand on the root word itself.

And its use of voiceless phonemes is sadly one that I can’t replicate very well in this medium. Not without speaking full phrases in an Eskaleut language, which I would butcher. So I won’t do that. But remember that phonemes are just sounds. And voiceless means that you are not using your vocal cords. For example, a voiced labial would be like the English letter ‘b’, but a voiceless labial would be like the English letter ‘p’. Eskaleut languages use voiceless plosives, fricatives, and nasals. Voiceless plosives are commonplace in many languages, they are typically labials, like the example I just gave. Voiceless fricatives are also fairly common, like the English letter ‘s’. Voiceless nasals are less common. You can count on two hands the number of languages globally that use voiceless nasals. Yupik is one of them, as are Icelandic, Burmese, and Welsh to name only a couple. A voiced nasal is very common - it’s the most common sound among all languages, like the English letter ‘m’. But that’s voiced, which means you use your vocal cords. A voiceless nasal means you block off using your vocal cords and push air through your nasal cavity instead. Voiceless nasals are always in conjunction with other phonemes and they create more of a stop than anything else.

OK. Are you still with me? We’ve got a handful more linguistic bits to celebrate, especially as we move into Central and South America. There are something like 185 languages spoken in central America and more than 500 languages spoken in South America. Many language families in Central and South America are isolated and endangered or extinct. Many languages do not belong to a bigger language family, or rather that much more research and study needs to be done before they can be grouped together. This is the downside of languages becoming extinct or endangered. When there are only so many living speakers of a language, it starts to die.

One of the larger language families in Central America is Oto-Manguean. These languages are spoken in central Mexico, like the regions of Oaxaca and Chiapas, as well as Honduras and Nicaragua. One very differentiating linguistic feature is the use of whistling language. Other languages do use whistle speech, but not as pervasively as in Oto-Manguean. Whistle speech in these languages stems from being tonal. You may have heard of tonal languages before. The most widely-spoken languages in the world are tonal, like Mandarin, Cantonese, Thai, Vietnamese, but also Punjabi, Yoruba, and Igbo. Many Oto-Manguean languages lack labial consonants, like Tlingit. There are few ‘b’ or ‘f’ sounds. Their tone system, however, provides a great level of complexity to the languages. In tonal languages, there are register tones and contour tones. You also use the pitch of a tone to differentiate.

So, a five level tone language will simply have 5 tone registers. You might say the phoneme ‘cha’ in these five different registers to convey completely different words. The Chinantec language has this kind of tone system. But tone systems can use multiple registers plus contour tones. An example of a mixed tone system is in the Trique language. In Trique, there are three register tones and five contour tones: high, mid, and low (registers), plus high-mid, mid-low, low-high, high-higher, and higher-highest. Tonal languages can also only use a tone on a stressed syllable. Some languages put the stressed syllable at the front of a word, others on the second syllable. The difference between ga-RAge and GA-rage.

Whistled speech means that you’re not using phonemes, just the varying tones of word combos and phrases. Information can be transmitted much further this way due to how sound travels. And in central Mexico, with its high elevations and volcanic valleys, this comes in especially handy. Culturally, whistled speech in Oto-Manguean languages is very important. Men do not shout, but they do whistle. It’s considered very rude to shout, and yet whistling can convey whole paragraphs of information without being rude or offensive, culturally speaking. Traditionally, it was the men who used whistle speech and not the women. One example of how language is inherent to its culture as well.

Another language family that includes multiple languages is Chibchan. These languages are spoken in the countries of Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, and Columbia. One of the languages spoken in Panama and Costa Rica is Guaymi. This language also involves cultural norms in its use of language. Specifically, long silences and vague speech is extremely common. In fact, it is considered very rude to not allow the person you’re speaking with enough time to respond. Considering your words before speaking them is just as important as the words themselves. While Chibchan languages do not use whistled speech, they do greet each other with the use of a grito. A grito is a cry or shout, where the first sound you make is held the longest followed by trills or modulations in the cry. It’s very common in Mexico and Central America.

The Chibchan language of Kogi is only spoken in a very remote section of northern Columbia. The Kogi people are the only known unconquered Andean civilization in the Americas. There are only just under 10k speakers of Kogi today. As a language, it is fairly simple. Kogi has seven different vowel sounds. It also uses labials, alveolars, palatals, velars, and glottals for its consonants. So the sounds of ‘p’, ‘t’, ‘k’, and their voiced siblings of ‘b’, ‘d’, ‘g’. Those are the plosives. The fricative sounds of ‘s’, ‘sh’, ‘x’, and ‘h’, and their voiced siblings of ‘z’ and ‘zh’. Also the sounds of ‘l’, ‘n’, ‘m’, ‘w’, and ‘j’. It is not a tonal language. The people and their culture are the only known pre-Columbian civilization to still exist without interruption. They live in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Maria mountain range and are descendants of the Tairona people.

The Tairona were an advanced civilization, having built stone walls and buildings, as well as gold jewelry and other objects they would hang from trees. The Tairona were forced into the highlands when the Caribe people arrived around 1000 CE. This was to their advantage when the Spanish arrived 500 years later. Their lifestyle and belief system centers around Mother Earth, with humans being her children. They do not regard their leaders as shamans, but rather mamos, which is the word for ‘sun’. It’s more around guidance and leadership, rather than medicinal or ceremonial healing. They have distinct roles for men and women, like the women being the ones who would pick cotton and make the fibers, but the men being ones to use the fibers to weave cloth. Chewing coca leaves is a strong custom for the men of the tribe. Farmland and livestock is passed from mother to daughter and father to son. Marriages are mostly arranged, but never forced. Family names are matrilineal. The villages in the mountains produce enough for what the community needs, so there is little to no need for contact with the outside world.

Another large language family, with many of the languages being isolated from the outside world, like the Kogi, is the Tupian family. There are roughly 70 Tupian languages, ranging from southern Colombia to northern Argentina. The bulk of Tupian languages are in Brazil, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Uruguay. When the Portuguese first arrived in Brazil, they noticed the indigenous people up and down the river systems spoke similar languages. The most well-known of these was Old Tupi. But old Tupi did not resist the influence of Portuguese as well as other Tupian languages. Like Guarani. In neighboring Spanish colonies (Paraguay and Bolivia), Guarani resisted the influence of Spanish and guarded itself linguistically.

Half the rural population of Paraguay still speaks Guarani today. And they are monolingual, meaning they do not also speak Spanish. One of the distinguishing markers of Guarani is its nasal harmony. And yes, I’m speaking of phonology now. Syllables used in Guarani are usually a consonant plus a vowel, or simply a vowel alone. A nasal syllable will use a nasal vowel, and if the consonant in the syllable is voiced, it will take on a nasal allophone. What’s an allophone? Great question! An allophone is one of multiple possible sounds or signs to produce a phoneme. For example in Spanish, you have the ‘d’ sound that differs from the words ‘dolor’ and ‘nada’. In Spanish, this is an allophone, but in another language like English, these are two different phonemes: ‘d’ vs. ‘th’.

Either way, this flexibility of the phonology makes Guarani much easier to speak, but specifically when it comes to using nasal vowels and consonants. As for its morphology, Guarani has a fun way of using tenses in nouns. Nouns use the nominal tense, i.e. the past and the future, but these two forms of the noun can also be combined. Using the past on a noun is a bit like saying ‘ex’ or ‘former’. So as an example of this mixed noun tense, you can say that someone studied to be a priest but never became one: the ‘ex-future priest’. Verbs also have some fun by using negation, instead of separate words to indicate a negative. As with the French language, Guarani uses a circumfix to express negation. In French, the example would be ‘je ne sais pas’. The use of ‘ne’ and ‘pas’ around the verb expresses negation. Guarani is similar, but the verb itself is transformed to add this circumfix: ajapó vs nd-ajapó-i (I make vs I don’t make).

Guarani words like jaguar, piranha, tapir, açaí, and jacaranda are used in English. Spanish words are also used in Guarani, an element of their interactions with the Spanish. Words for things the locals would have used often and possibly traded with the Spanish initially, like ‘queso’, ‘vaca’, ‘azucar’, ‘kanela’, and ‘cilantro’. Sadly, the Guarani were victims of colonization in the worst ways. They were murdered in droves and often stolen for the purposes of slavery. Sao Paulo was a large slave market for the Americas. The Guarani had their traditional bow and arrow as weaponry, the Dutch, Portuguese, and Spanish had gunpowder weapons. There was also the heavy hand of the Catholic Church, which extended into the reaches of remote villages to build missions. The Guarani survived, as did their cherished language, but it was a hard won battle.

On the other side of South America, the other side of the Andes mountain range, are the Quechuan languages. There are 46 languages in this family, including Hanan, Wanka, Urin, and Anqash Wamali. This is another example of a dialect continuum, rather than sharp language boundaries. Ranging from Ecuador, through Peru, into southern Bolivia, and the very northern parts of Argentina, Quechua is very widely spoken and was the language of the Incan Empire. When the Spanish first came, they actively encouraged the use of Quechua, which is a big part of why we have such a rich written and spoken history of the language. As you might be expecting, Quechua has borrowed a large number of vocabulary words from Spanish. And a large number of Quechua words have entered into English via Spanish: guano, condor, jerky, llama, poncho, coca, puma, quinine, and quinoa.

In Quechuan, phonologically, there are only three vowel phonemes and no diphthongs, also the stress is put on the penultimate syllable. Morphologically, there is heavy use of suffixes to change the overall meaning of a word. Interestingly, the language features bipersonal conjugation of verbs, evidentiality, and topic particles. Bipersonal conjugation means that the verb agrees with both the subject and object. The English sentence “We love wine” starts with the subject ‘we’ and the verb ‘love’ conjugates according to the subject. If we reversed the sentence and used ‘wine’ as the subject, the verb would conjugate differently: “Wine loves us”. In Quechuan, the verb conjugates in agreement with both subject and object.

Evidentiality refers to a morpheme that indicates the source of information. Quechuan uses three morphemes to mark evidentiality: -m(i), -chr(a), and -sh(i). The first marks direct evidence, the second marks inferred evidence or conjecture, the third marks hearsay or reported evidence. These morphemes are used as suffixes to express sentences like “ñawi-i-wan-mi lika-la-a” or “eyes I with see”, i.e. I saw with my own eyes. Using the second morpheme would imply sentences like “I think they will come back”. Using the third morpheme would make sentences like “I was told she borrowed it”. But evidential morphemes are not universally used in all situations and are sometimes omitted. The overuse of evidential morphemes is a sign the speaker lacks competence, either because they are not a native speaker or are, in very rare instances, mentally ill. Use of evidential morphemes is linked to the culture as well. It’s implied that a speaker who uses evidential morphemes effectively can be trusted, whereas those who don’t abide by customs and traditions are not to be trusted. Culturally, you want to assume responsibility through use of evidential morphemes only when you are certain and it is safe to do so. Doing this repeatedly builds your stature in a community also.

To geographically jump to another area of South America and chat about one fun linguistic oddity, we head to the Cariban language family. These languages are spoken in countries like Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana. Small callback to the Kogi people from earlier - these are the people who pushed them into the highlands of Colombia. There is one Cariban language, Hixkaryana, that is linguistically odd. This language has a default word order of object-verb-subject. This can sometimes lead to translations using what we call the ‘passive voice’ in English. The example sentence of ‘toto yonoye kamara’ can be directly translated as ‘man ate jaguar’. The passive voice English sentence would be: ‘the man got eaten by the jaguar’. However, the word order can also imply an English sentence translation of: ‘the jaguar ate the man’.

And Cariban languages are not to be confused with Caribbean languages. No, languages of the Caribbean are Arawakan languages, a large majority of which are now extinct. One of those extinct languages is Taino. It was one of the most widely spoken languages in the Caribbean, but within 100 years of European contact, it became extinct. It was, however, the first indigenous language ever heard by Europeans. Multiple words were borrowed into English, French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Dutch. The English words of ‘barbecue’, ‘canoe’, ‘guava’, ‘hammock’, ‘hurricane’, ‘iguana’, manatee’, ‘maroon’, ‘savanna’, and ‘tobacco’ are originally from Taino. Many place names are Taino in origin as well, like “Bahamas”, “Boriquen”, “Caicos”, “Cayman”, “Cuba”, “Haiti”, and “Jamaica”.

With so many indigenous languages of the Americas, it was difficult to trim this episode down. All extinct, endangered, and vulnerable languages need to be studied and cherished. Language develops as people develop, so it is a rich source of information for understanding people. What better way to celebrate and respect the people who were here first than to learn their languages. That was the very fun and ridiculously linguistic deep dive into the trivia question: How many languages are indigenous to the Americas?

Stay tuned for a brief intro to the indigenous language of the people, on whose land I currently live.

I acknowledge that I currently live on the land of the Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla. Their shared language is Upper Chinook, which sadly became extinct in 2012, with the death of its last-known living speaker: Gladys Thompson. The Endangered Language Archive has audio and video files of Upper Chinook, or Kiksht, being spoken. There are several dialects of Kiksht: Multnomah, Watlala, Wasco-Wishram, and Clackamas.

There were Lower and Upper Chinookan groups. The Lower and Upper distinctions were based on how far east or west the people lived along the Columbia River. Lower Chinook was spoken at the mouth of the Columbia River, Upper Chinook spoken where current-day Portland and Hood River are, which is closer to Mount Hood. They were not a large tribe and were immediately and deeply impacted by European contact, specifically by the diseases they brought. This would be the American history of Lewis & Clark.

However, a pidgin trade language known as Chinook Jargon still lives on today, although Critically Endangered. It developed in the late 18th century and broadened its base of speakers throughout the Pacific Northwest. Much of its vocabulary is based in Chinook, but 15% of it stems from French, and there are also English loanwords used. It uses glottal stops, ejectives, aspirated consonants, diphthongs, as well as labial, velar, alveolar, and uvular phonemes.

The language experienced a revitalization in Grand Ronde, Oregon in the late 1990s. In 2001, the tribe started an immersion preschool with funding from the Administration for Native Americans. A kindergarten was started in 2004, classes at the high school level began in 2011, and Lane Community College currently offers a two-year course of Chinuk Wawa. There are several Chinook words used by English speakers: ‘chuck’ which means water, can be seen in the Colchuck Glacier name; ‘mucky muck’ which means plenty of food, but is often used regarding an important person in the community; ‘potlatch’ which is a ceremony of exchanging gifts and sharing food, akin to the word use of potluck; ‘skookum’ which means strong or able and can often be used as an affirmative reply, “he’s a skookum guy” and “yeah, that’s skookum”; and ‘tillicum’ which means family or people.

Place names like ‘Alki Beach’ derive from Chinook, ‘alki’ means the future. Oddly enough, you’ll find place names of ‘Boston’ all over the Pacific Northwest, and that’s jargon meaning American (as opposed to British). The word ‘Chinook’ itself means the wind and is often used in place names. There are multiple place names using the word ‘lolo’ which means to carry. Also the word ‘mowich’ is used in multiple locations, this word means deer. The word ‘siwash’ is very common, even up into British Columbia, because this word means Native American man. You can put two jargon words together: Skookumchuck, which means big water or strong water, and you get the name of many a creek or river in the Pacific Northwest.

It’s been a fun endeavor to create these podcast episodes. For me and for whoever is listening. Not Trivial will be back after a hiatus with Season Two. More trivia to dig into, more history and language to unearth, more stories to tell. Please subscribe and listen wherever you find podcasts - and thank you very much for listening!