Whose death sparked the First World War?

We’ve all heard of World War One. And some of us have heard that the assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo was what sparked the war. Franz Ferdinand was the heir to the Austrian Empire. But have you heard of the 1889 murder-suicide in Mayerling, that led to Franz Ferdinand becoming the heir?

First, to set the stage for this murder-suicide in Mayerling. Let’s talk about the Austrian Empire. This is an empire born in 1804. The guy who founded the Austrian Empire was the Holy Roman Emperor, Francis II. Francis was also a Habsburg, which is a big deal in Europe. It’s one of the oldest ruling families, lots of Habsburg folks marrying each other, and lots of interesting characters in this family. Including one of Francis’ descendants. So, the Empire is humming along (not really) and a guy named Franz Joseph I comes on the scene. He’s young, very young when he becomes Emperor of Austria. And oh, by the way, this empire is bigger than the country of Austria is today. It includes what is now the Czech Republic, Slovakia, parts of Poland and Ukraine, Hungary, parts of Romania and Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, and even northern Italy. Franz Joseph I is 18 when he becomes Emperor. And not because his dad dies, but because his dad is ousted. For being incompetent, essentially. So, there’s that. Already we’ve got drama.

Franz Joseph also becomes Emperor in the year 1848, which if you know about European history is a big year for revolutions. Lots of upheaval, crowds with lit torches storming buildings, industrial areas going on strikes, but also the bourgeois middle classes making impassioned speeches for democracy and liberal reform. Think Les Mis. People want change. It’s not an easy hand-over of power and it’s tumultuous. Just six years into being Emperor, Franz Joseph survives an assassination attempt. A knife to the throat. Yikes! Franz Joseph needs stability, he needs strength for his empire, he needs an heir. He marries a beautiful Duchess of Bavaria called Elisabeth, AKA Sisi. She is still regarded as one of the most beautiful women of the 19th century. Sisi had dark, magnetic eyes and long, wavy chestnut hair, which she kept healthy and clean for all of her life. And when I say long, I mean she was 5’8 and she had ankle-length hair. Anyway, he’s 25, she’s 16. Which is fairly common during this time, remember. The two are actually madly in love, even if their relationship would eventually get a little complex later in life. And there’s a lot riding on this marriage. Sisi is pressured to produce an heir, and she does become pregnant pretty quickly. But instead of the boy everyone wants, it’s a girl. And Sisi’s mother-in-law, Franz Joseph’s mom Sophie, is being an overbearing tyrant when it comes to family affairs. Even going so far as to raise Sisi’s child as her own, even named her after herself, Sophie. Sisi starts to have health problems, experiencing anxiety and paranoia. She has random coughing fits and just isn’t cut out for the court life in Vienna. And of course, as we all know, women can just choose whether or not they birth a boy or girl. Plus, stress is totally welcome in the whole process of pregnancy and birth, right? Sisi is trying her best, but her next pregnancy a year later also produces another girl.

And yet, the Empire is chugging along. The family takes a trip to Hungary, which during this time was under pretty severe martial law and was always trying to become its own country. Somehow during this trip, Sisi made such an impression on the local people, that the powerbrokers in Buda and Pest praise and celebrate her as a friend of Hungary. She is still revered in parts of the country today. This trip and Sisi’s triumph begins a decade-long process of Austria and Hungary coming to a sort of compromise. You’d think Sisi would garner some praise in Vienna for her efforts, but no. She is still not fulfilling her only job, to produce an heir. Meanwhile, this trip brings illness to their two girls, and their eldest, Sophie, ends up dying at age two.

The very next year, Sisi’s third pregnancy finally produces an heir, their son Crown Prince Rudolf, but the parents are exhausted. Franz Joseph has his hands full making sure his empire doesn’t fracture. Sisi is finally relieved she has completed her main task, but she’s also dealing with anxiety and depression. In a society that doesn’t believe in mental health. Her mother-in-law is raising her children, her husband is being defeated in battles with Italian provinces, so she retreats. Sisi had always been aware of her slim figure and often ate a restrictive diet in general. But at the height of her depression, she stopped visiting her husband’s bed, committed to tight-lacing, and reduced her weight to her desired amount of 110 pounds. The tight-lacing made mother-in-law Sophie angry, since that practice would have prohibited Sisi from becoming pregnant again. Three pregnancies in four years sounds tiring and hard. Don’t blame Sisi for wanting to take some measure of her life back for herself. Let’s be clear though. Sisi clearly dealt with an eating disorder her entire life, which is not healthy. Sisi’s attempts to be more herself sometimes went over smoothly, but more often backfired on her.

The birth of a son and heir makes her more influential and her support of Hungary in the ongoing talks satisfies her desire to not just be a doting, domestic wife. She served as a personal advocate for the Hungarian Count Andrassy, who would eventually become the Austrian Empire’s foreign minister decades later. Sisi is always described as eccentric, hyperactive, melancholic at times. She maintains interests in poetry, horseback riding, and generally being in nature. But every time she experiences a setback, like losing control of her son’s education and upbringing, her health would suffer greatly. Doctors often prescribed long restives to places like Madeira and Corfu. And every time Sisi came back to Vienna, her health would suffer again. We’re talking about tuberculosis-type illnesses. I am not a doctor, but successive pregnancies amidst a restrictive diet, aerobics, and tight-lacing. Let’s just say I’m not shocked her health wasn’t robust. She spent a couple of years away from Vienna, only coming back for her husband’s birthday celebrations.

Let’s shift to the heir, Rudolf… You can imagine what a young 5 or 6 year-old Rudolf is learning, growing up in such an environment with his dismissive, self-absorbed parents and interfering grandmother. Rudolf is being brought up to be a conservative, militaristic thinker and leader. Not a scholar or even an observer of the people of this Empire he was supposed to inherit one day. The Austrian Empire is an autocracy, as well as a monarchy. The Hungarian compromises were abnormal. Usually, it was harsh authoritarian rule only, with no excuses made. His education would often consist of emotional and physical abuse, as a tactic to try to make him submit to the way of thinking required of him. But Rudolf is more like his mother than his father. He’s sensitive and imaginative, as well as melancholic and self-destructive. He’s drawn to the natural sciences of minerals, rocks, and gems. Even started a collection, which would later become part of the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences in Vienna. He grows up with friends, but ultimately isolated. No brothers to lean on, only his older sister to confide in. And any struggle he encountered, would’ve been seen as a weakness. And Empires don’t run on weakness. Just ask Franz Joseph’s father who was replaced by his 18-year-old son.

Before we talk about the actual murder-suicide, we also have to talk about Rudolf’s marriage and sex life. When Rudolf is 22, he marries Princess Stephanie of Belgium. Stephanie is the second daughter, third child of King Leopold II. Leopold is infamous for being the sole owner of Congo during the latter half of the 19th century, effectively enslaving and torturing millions of Congolese for his own personal financial benefit. Leopold and Stephanie’s mother, Marie Henriette, didn’t like each other at all and were so dissimilar. It was a complete mismatch, a marriage built on political convenience, and against both of their wishes. Stephanie also experienced the death of her older brother when she was five, watching him die in their mother’s arms from a childhood illness. This mourning period never really left her, and she also fell ill a few years later with typhus. She ultimately recovered, but it was touch and go for a while. Her parents had prepared for her death and Stephanie herself probably felt as if it would occur. And yet, she survived. This type of trauma didn’t help her parent’s marriage, which fell apart further, after an attempt for another male heir resulted in a baby girl. Her father Leopold distanced himself, spent time with mistresses and not his family. Stephanie’s upbringing was strict and disciplined, her education was rudimentary at best. She was being groomed for a politically advantageous marriage. When Stephanie and Rudolf finally married, both sets of parents were enthused. Austria would have more descendants, more heirs, more stability. Belgium, a country barely 50 years old, would have wed itself into one of the most senior and influential families in Europe, the Habsburgs.

Rudolf and Stephanie, at first, were invested in sustaining a happy marriage. They were both persuaded into marrying, understanding their familial duties, but they were also children of parents who didn’t really get along most of the time. Especially Stephanie. The pair tried their best to get to know each other better, create a supportive relationship, they even had nicknames for each other. But it didn’t last long. Rudolf had mistresses prior to their engagement and wedding, and yet ensured that Stephanie never left the palace with him. He always seemed suspicious, snuck off to do what he felt he needed to do, and went through bouts of paranoia and depression, even bursting with violence sometimes. Sisi also made Stephanie go on important public appearances with Rudolf and Franz Joseph, while Sisi retreated further away from public life. With Stephanie on Franz Joseph’s arm for hostessing, Rudolf started to withdraw from his wife. However, they knew their duty was to provide children for the empire. When Stephanie became pregnant in 1883, both were sure it would be a boy. I’ll let you guess what actually happened… Yep. After their daughter was born, their marriage started to crack and fall apart.

Rudolf began visiting a great number of mistresses, as well as hosting parties with guests who were the opposite of his father’s politics. He even went so far as to anonymously publish his liberal political leanings and ideas in a Viennese newspaper. A couple years after his daughter’s birth, Rudolf fell seriously ill. Doctors were diagnosing all sorts of maladies, but ultimately, they knew he had been infected by a venereal disease. They just weren’t sure which one. Syphilis was a pretty serious contender, and would have been the most tragic consequence for the heir to the Austrian throne. Plus, Rudolf had no heir yet. They gave him morphine, opium, and even mercury - which if given in large enough amounts can result in neurological and cognitive dysfunction. But, of course, because VD is taboo, nobody told Stephanie about what the doctors suspected. And while the couple were away from Vienna focused on Rudolf’s health, they engaged in more sex, hoping to have another child and possible heir. But Rudolf ended up infecting Stephanie, because she became very ill and was eventually found to be sterile. As you can imagine, Stephanie resented her husband from then on. Rudolf could no longer produce children through his marriage to her. Stephanie could no longer bear children, something she had longed for, to be a mother of many. The two tried to be civil towards each other, but Stephanie’s bitterness and emotional lashing out at Rudolf made him dive deeper into his debauchery.

They began to live separate lives. Stephanie focused on her daughter, Elisabeth Marie, and even fell in love with a Polish count during a visit in 1887. She didn’t hide it at all from Rudolf, who also continued his liaisons with a mistress. And yet, she could see that Rudolf was spiraling into his depression. Stephanie went to Franz Joseph to try and make the Emperor see how “pathetic” and “unstable” Rudolf had become. And because this wasn’t news to dear old dad, Franz Joseph brushed her off, effectively telling her that Rudolf was fine and that she was “imagining things”. Little did anyone know, Rudolf was indeed spiraling and just months away from his own death.

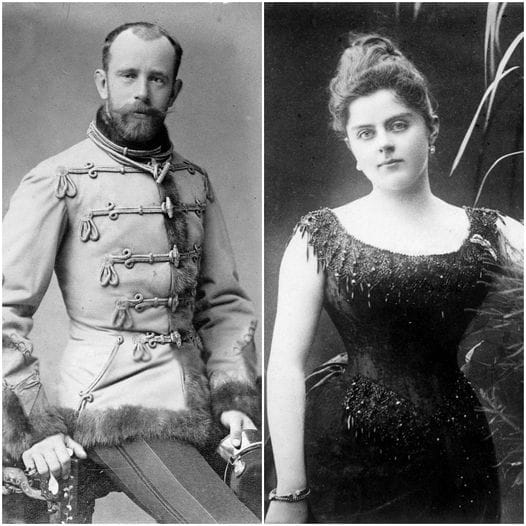

By the summer of 1888, Rudolf had been in a long-term relationship with an actress named Mitzi. And he was contemplating taking his own life. Where the idea of a suicide pact came from, we may not know, but Rudolf was determined. When he talked about a suicide pact with Mitzi, she laughed at and rebuffed him. Effectively severing their relationship. In the fall of 1888, Rudolf met a Baroness named Mary Vetsera, who was just 17 years old. Mary was obsessed with Rudolf and swiftly began an affair with him. Her family, mostly her sister and mother, were enraged and thought she was being foolish. But she was determined to be whatever Rudolf wanted. So now we have two determined lovers, absorbed in their shared melancholy.

Ultimately, what Rudolf wanted was to die, but not alone. On January 29th, 1889, Sisi and Franz Joseph hosted a family dinner party. They were about to leave for Hungary two days later, so this was a regular dinner with family before a long trip. Rudolf excused himself, claiming to be indisposed. Which is 19th century code for “I’m busy and just not into it”. The family may not have seen this as a red flag at all. To the family, it was disappointing, but not irregular. Rudolf traveled to his hunting lodge in Mayerling, less than 20 miles from the palace in Vienna. He had made plans with friends to go hunting on the next day, the 30th. This also would have given him cover for his family not to suspect what would occur during the night of the 29th.

In the morning of the 30th, when Rudolf’s valet went to his room at the lodge, to wake him up for the hunt, he found the room locked and heard no reply from Rudolf. He knocked repeatedly and called out for the Crown Prince. Nothing. Another hunting companion, Joseph, joined in, having heard the valet try to wake Rudolf. Eventually, the two broke the door open with a hammer. What they saw would precipitate a number of events nobody could have foreseen.

The Crown Prince Rudolf sat leaning next to the bed, blood seeming to come from his mouth. 17-year-old Mary was dead on the bed itself, rigor having already set in. The room was shuttered, so no natural light could come in. Joseph and the valet also saw an empty glass by the bedside. The valet knew that the poison strychnine could cause internal bleeding, and immediately thought that Mary had poisoned Rudolf and then killed herself. Joseph immediately ran to the nearest train station and quickly got back to the palace in Vienna. The imperial family lived a life of protocol - and even Crown Prince Rudolf’s death went through all the layers of rigid palace protocol. First, to the Emperor’s chief military officer at the palace. Then, to the Controller of the Empress’ household. The thought was that only Sisi could inform Franz Joseph of such terrible news. So the Controller searched for Sisi’s favorite lady-in-waiting. And this lady-in-waiting interrupted Sisi at her Greek lesson, in order to break the news to her that her only son was dead. Aged 30. Sisi then informed her husband. The two parents must have both been adrift in the grief and shock for some time. Sisi, ultimately, fell into a deep and despairing state of depression. Those closest to her even thought she might commit suicide as well, in the months afterward.

The police service was immediately called to the hunting lodge. Mary’s body was taken from the place, interred very quickly, and her own mother wasn’t even allowed to go to the burial. A statement on behalf of the Emperor was given that the Crown Prince had died from a heart aneurysm. The entire Imperial family believed he had been poisoned. The palace attempted a major cover-up. Lying that Mary had also died, but on her way to Venice instead. Suicide was a big Catholic sin, still is for many, so the story of Rudolf having died from natural circumstances had to stick. When the press descended on Mayerling, they quickly learned that Mary was implicated in Rudolf’s death. Because people talk. Suddenly, his heart aneurysm was found out to be a lie. The Emperor is now having to make very public decisions, while also grieving his son’s death. Ultimately, after a more thorough examination of Rudolf’s body, the announcement of his death was amended. It was made clear that Rudolf had shot Mary, sat by her body for some time, before then shooting himself. Murder. Suicide. The press had a story that Franz Joseph had argued with Rudolf about giving up his mistress, the young Baroness Mary Vetsera. They ran with the story of star-crossed lovers, not meant for the confined lives of the court, and a snap decision made by Rudolf in a moment when “the balance of his mind was disturbed”.

But really, this event was planned in advance. Rudolf even wrote a note for Stephanie: “Dear Stéphanie, you are delivered from my fatal presence; be happy in your destiny. Be good to the poor little one who is the only thing left of me. I calmly enter death which alone can save my good reputation. Kissing you with all my heart, your Rudolf who loves you.”

Franz Joseph, however, played into the idea that Rudolf was in a mentally fragile place. He did so, as a Catholic, who wanted to bury his son in the family crypt, which was holy ground. A deliberate suicide would have prevented this. A special dispensation from the Vatican was allowed. Rudolf was buried in the Imperial Crypt, next to hundreds of other Habsburgs. As opposed to where Rudolf himself wished to be buried: next to his mistress Mary Vetsera in a common cemetery. But the story that Franz Joseph had argued with Rudolf, and so spurred him into a delicate state of mind, wasn’t believed by many of the Emperor’s family and friends. Queen Victoria’s daughter, the Empress of Germany, wrote to her famous mother that she didn’t believe Franz Joseph to have argued with Rudolf: “Prince Bismarck told me that the violent scenes and altercations between the Emperor and Rudolf had been the cause of Rudolf's suicide. I replied that I had heard this much doubted. I did not say what I thought, which is that for thirty years I have had the experience of how many lies Prince Bismarck's diplomatic agents (with some exceptions) have written him, and therefore I usually disbelieve what they write completely.” Tangent sidenote: sounds like the German Empire has its own pre-world war shenanigans going on!

Anyway… The aftermath of Rudolf’s death was both tragic and a real crisis. The Austrian Emperor had no direct male heir. Franz Joseph’s younger brother, Karl Ludwig, was announced as the heir presumptive. Karl Ludwig had several children, three boys and three girls. His eldest son was named Archduke Franz Ferdinand, who was groomed from that point on, to eventually become the Austrian Emperor. Karl Ludwig died of typhoid in 1896, which made Franz Ferdinand the heir apparent to Franz Joseph.

In June 1914, Franz Joseph commanded Franz Ferdinand to observe military maneuvers in Bosnia, Sarajevo specifically. His wife went with him, fearing for his safety. They were to subsequently appear at the opening of the state museum in Sarajevo, as well. Their assassination on the 28th of June 1914 was the spark that started the First World War. Franz Ferdinand was the unlucky target, in part due to the stifling expectations put upon Empress Sisi and her son Rudolf. It’s unlikely the First World War could have been avoided if Rudolf had lived. But the steps leading up to the war could have been different. Perhaps, if Rudolf had lived, Franz Joseph would have made Rudolf be the one to visit Sarajevo. And could very well have been the target. Which would have meant Franz Ferdinand could have succeeded to the throne as the next male descendant anyway. As it happens, Franz Joseph didn’t live much longer than his nephew, Franz Ferdinand. He died at the ripe age of 86, just two years after declaring war on Russia in August of 1914.

And that’s the deep dive into Archduke Franz Ferdinand being an answer to the trivia question: Whose death sparked the start of the First World War?

Short recap on the women of this tale. We have Empress Elisabeth AKA Sisi, the wife of Emperor Franz Joseph. We have Princess Stephanie, the wife of Crown Prince Rudolf. AND we have Elisabeth Marie, Rudolf’s daughter.

As previously stated, Empress Sisi never recovered from Rudolf’s death. His death was only one of many others. Her father died a year prior to Rudolf. Her sister Helene died a year after Rudolf. As did the Hungarian Count Andrassy, who had been her one political friend. Her mother died two years after Helene. And her other sister died five years after her mother. She insisted on never spending much time in Vienna. She had a warm friendship with her husband, but it never again became anything more than that. In 1898, Sisi was traveling to Geneva, Switzerland. On September 10th, Sisi and her lady-in-waiting left their hotel and walked together to where a steamer was waiting on the lake for its passengers. Before they made it to the steamer, an anarchist named Luigi Lucheni approached them, seemed to stumble and made a movement with his hand, as if he wanted to maintain his balance. When really, he had stabbed her with a sharpened needle file that was 4 inches long. Initially, due to her tightly-laced corset, the wound didn’t make as big an impact as you would think. Sisi managed to walk and board the steamer before collapsing and losing consciousness. She was helped to a bench on board, her coat removed and her corset loosened. The thought was that she had fainted due to the heat of the steamer. But when a tiny drop of blood was discovered on her chest, the captain was informed of her identity, turned the boat around, and she was carried back to her hotel. She likely died en route back to the hotel. Franz Joseph was devastated, unable to understand how someone could murder a woman with such a generous heart. Elisabeth's will stipulated that a large part of her jewel collection should be sold and the proceeds, then estimated at over £600,000, were to be applied to various religious and charitable organizations. Everything outside of the crown jewels and state property that Elisabeth had the power to bequeath was left to her granddaughter, the Archduchess Elisabeth, Rudolf's child.

After Rudolf’s death, Princess Stephanie became the Dowager Crown Princess. She desperately wished to leave Vienna, to run back to her parents in Belgium. But neither her father nor Franz Joseph approved. She was her daughter’s guardian, but she would flee Vienna as often as she could, with permission. She would go to Miramare Castle near Trieste and withdraw from public life completely. Which meant she was away from her daughter, without much contact. Initially, she continued her affair with the Polish count. But his health failed at the young age of 40, and with her lover’s death, Stephanie was once again in a deep grief. Sisi and Franz Joseph avoided her. Her previous friendships faded. She escaped into theater plays, operas, and painting. She went on long visits to places like Corfu, Sicily, Malta, as well as Scandinavia, then Greece and Palestine a few years later, and Russia after that. When Sisi was killed, Franz Joseph and Leopold, Stephanie’s father, thought up a plan to remarry Stephanie to Franz Ferdinand. Luckily, Franz Ferdinand married his own lover. Which meant Stephanie got to marry a low-ranking aristocrat in 1900, someone who shared her love of art collecting, travels to distant lands, and perfecting their castle’s gardens. Her father disowned her for marrying below her rank and Franz Joseph dissolved her household in Vienna. Stephanie and her new husband settled into a mansion in what is now Bratislava, Slovakia. They received many guests there, writers of the day, and some family members, but not many. Stephanie was happy. When Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and the World War began, Stephanie set up a makeshift hospital in her mansion. Her husband took a position with the Red Cross. They survived the war together. The Austrian Empire did not survive. In 1923, Stephanie started writing her memoirs, but the process was a long one. Her book “I Was To be Empress” wasn’t published until 1935. It was initially censored in Austria, but sold practically everywhere else. In the book, she published Rudolf’s last letter to her, essentially confirming that they had made a suicide pact. Stephanie and her husband also endured World War Two. Their castle was supposed to be a military hospital for wounded soldiers of the German army. But by 1945, it was the Soviets who occupied their area. The pair retreated to a nearby Abbey and took refuge. Only three months later, Stephanie died of a stroke, aged 81. Her husband only lasted another year without her, and they were buried together on the Abbey grounds. A fitting end for a woman who had been so wronged by high society.

As for Rudolf’s daughter, Elisabeth Marie, she shared her mother’s disdain for the Viennese court. She grew up headstrong and opinionated and full of contempt for people who she thought should be kinder to her. Like her grandmother, Sisi. So when Sisi’s will bequeathed a small fortune to Elisabeth Marie, she was surprised. This inheritance also meant her relationship with her dependent mother, Stephanie, became strained. Elisabeth Marie disapproved of her mother’s remarriage, and eventually cut ties with her mother, whom she once had a very strong connection to. The same year her mother remarried, Elisabeth Marie met Prince Otto Weriand at a ball. He was ten years older than her, below her in rank, and she had eyes for him. She convinced her grandfather, Franz Joseph, that they should be married. And he ultimately relented. Unluckily for Otto, who had already proposed to a lovely Countess, he was dumbstruck when Franz Joseph informed Otto that he was to marry Elisabeth Marie. But when the Emperor orders you, you comply. As you can imagine, the marriage wasn’t a success. The pair did manage to have four children: three boys and one girl. However, Elisabeth Marie only reminded Franz Joseph and others of her late father. Shortly into their marriage, some misunderstanding or complete fabrication persuaded Elisabeth to believe her husband was having an affair with an actress. Elisabeth did what any opinionated and stubborn modern woman would do. She somehow got hold of a pistol and shot the actress, who later died of her wounds. While Franz Joseph was still alive, Elisabeth and Otto settled into a familiar pattern of not being around each other and having their own love affairs outside the marriage. Once the monarchy dissolved, the pair separated officially. Very soon after, Elisabeth Marie was a member of the Social Democrat Party, and was nicknamed “the red archduchess”. She met a committed politician and committee member named Leopold. While she was not divorced, which wasn’t allowed under Catholic law at the time, she started a life with Leopold. She won custody of her children, through any means necessary. She fully committed herself to the socialist cause. Leopold wasn’t well-liked and he often bent the rules, or broke them. He was arrested and imprisoned by the Austrian government in 1933. And again in 1944 by the occupying Nazi German government. At that point, he was sent to Dachau concentration camp outside Munich. He only left after the camp was liberated by the Americans in 1945. It wasn’t until after the Second World War, that the two were married, after her divorce was finally granted twenty-one years after her separation from Otto. But post-war Vienna was still occupied, first by the Soviets and then by the French. Elisabeth and Leopold didn’t return to their villa until Allied occupation ended in 1955. By then, they were both in poor health, with poor Leopold dying in 1956 from a heart attack. Elisabeth was confined to a wheelchair at that point, and became a recluse who bred German Shepherds until her death in 1963. She was 79. Oddly enough, Elisabeth had been able to keep personal belongings through both world wars. On her deathbed, she insisted on any item that had previously belonged to the Imperial family - all the sculptures, paintings, furniture, documents… family heirlooms - be given to the Republic of Austria. They are housed in museums around Vienna today. This last act of grace has allowed us all to know the history, see it in museums, and learn about it again. Just like you and I are doing now.