What important cultural movements existed in Germany between the two World Wars?

We’ve all heard of Germany’s militaristic past. And some of us know a lot about either Kaiser Wilhelm or Adolf Hitler, the two men at Germany’s helm at the start of both 20th century World Wars. But did you know that between the two World Wars, Germany was actually a hotbed for absurdist and avant-garde art, organic farming and nudism, as well as expressionist film and literature?

Welcome to Not Trivial! A podcast that takes a deeper dive into the stories behind the trivia questions you might’ve heard at the pub. My name is Liz, and I’ve been a trivia nerd since I was young. My parents and I would play Trivial Pursuit very often. Still do. I’ve hosted pub trivia, I’ve played pub trivia, and I’m a collector of random history, language, and world culture facts. One of my greatest passions is sharing what I’ve collected with others. I’m hopeful this podcast makes the trivia questions feel less trivial, and more important to understanding how the past creates the present, and subsequently the future. Let’s get started…

Get ready for some interesting tidbits about some interesting artists in this episode! We will get to that good stuff in a little bit. Before we dive deep into the avant-garde funk of this time period, let’s start with some specifics, like when is this time period? The period of time between World War I and World War II is referred to in a few different ways. The interwar period, or interbellum. Also referred to as a period of rising fascism in Europe. The Roaring Twenties, or Jazz Age, is a term you’ve likely heard before. The Great Depression of the 1930s. It’s also part of the Machine Age (1880s to 1940s), which included up until World War I, the Second Industrial Revolution AKA the Technological Revolution. There was a lot going on around the world during the early 20th century. To say the least.

The First World War, also called the Great War, did not conclude with a “winner” and a “loser”. The war came to an end because the parties involved, the final one being Germany, agreed to an armistice. Kaiser Wilhelm abdicated to avoid an outright mutiny of the German army. Empires fell, including the Ottoman Empire, Russian Empire, German Empire, and Austro-Hungarian Empire. New states came into being, including Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia. The First World War came to an end in November of 1918.

The Second World War in Europe began when German forces invaded Poland in September of 1939. This is generally accepted as the “start of the war”. But really, the years of 1914-1945 are also referred to as the Second Thirty Years War. This is because there were conflicts around the world throughout the 1920s and 30s. The Spanish Civil War from 1936-39, the Second Italo-Ethiopian War from 1935-37, the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, the Chinese Civil War from 1927-1949, the Rif War in Morocco from 1921-26, and US incursions into and occupations of countries like Panama, Cuba, Nicaragua, Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

To say this interbellum period was a stable time is a myth, it’s an illusion. But there was absolutely a certain zeitgeist of abundance, letting loose, and individualism. There was a boon in sports, with the building of large arenas and stadiums. The Olympics were idealized and national Olympic committees popped up in various countries around the world. The formation and growth of FIFA as an organization helped football, i.e. soccer, become the world’s game. Women’s suffrage became a reality in countries around the globe during the 20s and 30s, including in the Netherlands, Uruguay, Canada, Britain, the USA, Ireland, Cuba, Brazil, Thailand, and the Philippines. Many more countries saw full suffrage for women at the end of WWII.

In Germany, this interbellum period is split between two republics: the Weimar Republic from 1918-1933, and the German Reich from 1933-1945. We’re going to focus on the Weimar Republic today. Germany was devastated after the First World War, in terms of a generation of young people being killed in action, as well as hyperinflation and economic hardship. The financial duress Germany faced was directly linked to the terms of the 1920 Treaty of Versailles, which forced Germany to pay reparations in the neighborhood of $440 billion in 2023 US dollars. That’s crippling to an economy, especially one that had been built on factories pumping out machinery and weapons. Remember - Second Industrial Revolution.

German political extremism was also at an all-time high - and that was even before Hitler came on the scene! Something Hitler very likely tapped into and manipulated to his advantage. The Weimar Republic was able to stabilize its economy somewhat, and even have some healthy diplomatic relationships with other countries. But the Great Depression immediately left its mark on a very fragile economic and political structure. Germany, at the time the Depression started, leaned heavily on the US for financial loans. It had not paid back its WWI reparations and had in fact defaulted on those payments by the mid 1920s. Once the Depression hit, Germany now owed America payments on its loans on top of those reparations. Hitler utilized a growing resentment felt by Germans and its reliance on other countries, in order to launch his chancellorship in 1933. Bonus fact: Germany didn’t ultimately pay its WWI reparations in full until 2010.

We’re getting a sense of the stage set for the rebellious and raucous cultural movements during the Weimar Republic. The Weimar culture is centered around the city of Berlin. During the 1920s, Berlin became the third-largest metropolis in the world. It was chaotic, creative, intellectual, and passionate. All sorts of artists and scholars and big thinkers were part of Berlin society. The city was seen as a left-wing stronghold. But back then, that meant communism and it was referred to by rightists as “the reddest city after Moscow”. Nazi fascists and communists got into street fights and bar brawls on a regular enough basis, with each side trying to goad the other into violence.

Berlin in the Golden Twenties, as they called it then, was a study in social contrasts. A large portion of its population struggled to find steady employment, and yet a growing middle class and wealthy upper class set out to define Berlin as a cosmopolitan city. With all the comforts and ideals a city of its size should offer. You might see elephants on parade as they made their way from a circus show to the Berlin zoo. You might see an impromptu jiu-jitsu or boxing match in the Lustgarten. You might see giant zeppelins hovering slowly above the city skyline. Not to mention numerous race car races in the forested outer edges of the city. While these kinds of social sights and events were more and more commonplace in 1920s Berlin, it was also commonplace to see rampant prostitution, drug use, and petty crime. Berlin began to carry the reputation of being a “cesspool”. At one point, over 60 gangs tried to corner the black markets for heroin, cocaine, tranquilizers, and sex workers.

If you’re a curious human being, I bet you’re dying to have lived in 1920s Berlin for just one day. Just to understand how hectic, erratic, or wild it would’ve been. Am I right? I’m right…

Let’s expand now into exactly how absurd and avant-garde interbellum Berlin was. And yes, there’ll be some of what we think of as rebellious and wild - there’ll also be some grounding in what Germans were thinking and feeling during this time of explosive culture. The fields of architecture and design, film, literature, painting, music, philosophy, psychology, fashion, and even science all experienced creative bursts of innovation and growth during the Weimar Republic. In 1921, Albert Einstein was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics and served as the director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics until the Nazis rose to power. Physician Magnus Hirschfeld established the Institute for Sexology in 1919, which remained open until 1933. Hirschfeld was a vocal advocate for homosexual, bisexual, and transgender legal rights for men and women, repeatedly petitioning parliament. There were also foundational contributions to quantum mechanics made during the late 20s, such as Werner Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle and the invention of Matrix mechanics. Research into aero- and fluid-dynamics propelled the creation of more drag-efficient jets. Something the Nazis were A-OK with. They destroyed Hirschfeld’s institute, on the other hand.

If there’s a new movement in culture, it can’t happen without big thinkers. Let’s talk philosophy first. Germany's most influential philosopher during the Weimar Republic years, and perhaps of the 20th century, was Martin Heidegger. Heidegger published one of the cornerstones of 20th-century philosophy during this period, Being and Time (1927). In this fundamental text, "Dasein" is introduced as a term for the type of being that humans possess. Dasein has been translated as "being there", or “existence”. It’s a type of being that must confront mortality, personhood, and the paradox of living amongst other beings but ultimately being alone. Being and Time influenced successive generations of philosophers in Europe and the United States, particularly in the areas of phenomenology, existentialism, hermeneutics and deconstruction. Heidegger's work built on, and responded to, the earlier explorations of phenomenology by another Weimar era philosopher, Edmund Husserl.

But other philosophers have criticized Heidegger, saying that Dasein is an idealistic retreat from historical reality. Heidegger is criticized for creating a conservative myth of being - and it’s true that Heidegger utilized his philosophy to promote Hitler to his chancellorship in 1933. Heidegger himself, had affairs, one of them with a 17-year-old Hannah Arendt. When he was a 35-year-old married man with two sons. Hannah Arendt is important to mention here, because she was a student of his and ultimately became one of the most influential political theorists of the 20th century. She was also Jewish. Hannah was raised in a progressive family, her mother being a passionate Social Democrat. Once Hitler came to power in 1933, her work and research into antisemitism got her arrested and held by the Gestapo. Ultimately, she escaped to Paris, and then New York. It was in New York post WWII, that her insight and research into totalitarianism, authority, direct democracy, and the nature of power and evil, brought her to the world’s attention. Specifically, and I realize this is very much after the Weimar period, but her testimony during the trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961 is remembered for its controversy. To many, her explanation of how ‘ordinary people’ become main actors in a totalitarian system sounded like a defense of his actions.

The intersection of politics and philosophy inspired other philosophers in Weimar Germany, when radical politics included many thinkers and activists across the political spectrum. Herbert Marcuse was a student in Freiburg, where he went to study under Martin Heidegger. Marcuse himself later became a driving force in the New Left in the United States. Specifically, he attempted to find the overlap between Marxism and Heidegger’s Dasein ideas. Ultimately, Marcuse became a proponent of the socially marginalized. Not because he had a bleeding heart and felt himself a liberal, as we think of it today, but because he saw modern technology, communism, and capitalism as agents of human repression. Marcuse argued that industrialization pushed factory laborers and workers to see themselves as extension of the objects they produced.

Germany during the Weimar Republic was also health-conscious. Health treatments, some more questionable than others, were also enduring innovation in Germany, in the decades leading up to World War I. As a group, they were collectively known as part of the Lebensreform, or Life Reform, movement. During the Weimar years, some of these found traction with the German public, particularly in Berlin. Some innovations had lasting influence. German-born Joseph Pilates developed much of his Pilates system of physical training during the 1920s. Nacktkultur, called naturism or modern nudism in English, resulted in resorts for naturists established at a rapid pace along the northern coast of Germany during the 1920s. The island of Sylt, which had been a military outpost during WWI, became the first Freikorperkultur mecca for Germans and other Europeans in the 1920s. Ease of access was heightened by the addition of a rail causeway, known as the Hindenburgdamm. Yes, the same Hindenburg name as the zeppelin that exploded in 1937. He’ll be back in our story later on today. Back to the beach… The bathing beaches on Sylt were separated into the ‘ladies bath’ and the ‘mens bath’. Nude beaches on Sylt became famous, still even into the 1960s. The beaches designated as nudist or naturist, started to blend into the “normal” beaches. It’s currently not unusual to see nude bathing on beaches around Germany, and in fact around Europe.

On the other end of the spectrum of health and self-improvement, philosopher Rudolf Steiner, had an enormous influence on the alternative health movement before his death in 1925 and far beyond. He was an early proponent of organic agriculture, in the form of a holistic concept later called biodynamic agriculture. In 1924 he delivered a series of public lectures on the topic, which were then published. Aufklärungsfilme (enlightenment films) supported the idea of teaching the public about important social problems, such as alcohol and drug addiction, venereal disease, homosexuality, prostitution, and prison reform. We can thank the Germans, yes, for pioneering public health service videos.

So far, we’ve got big thinkers, big health nuts, now to the big artistry. Several major movements in the fine arts were in the midst of peaking during the 1920s. German Expressionism had begun before World War I and continued to have a strong influence throughout the 1920s.

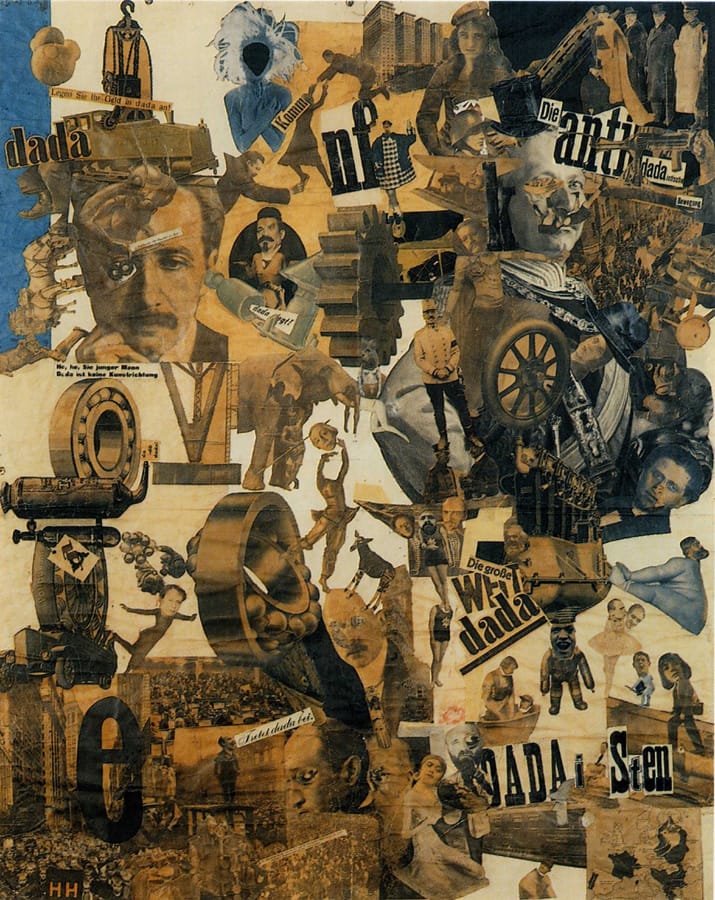

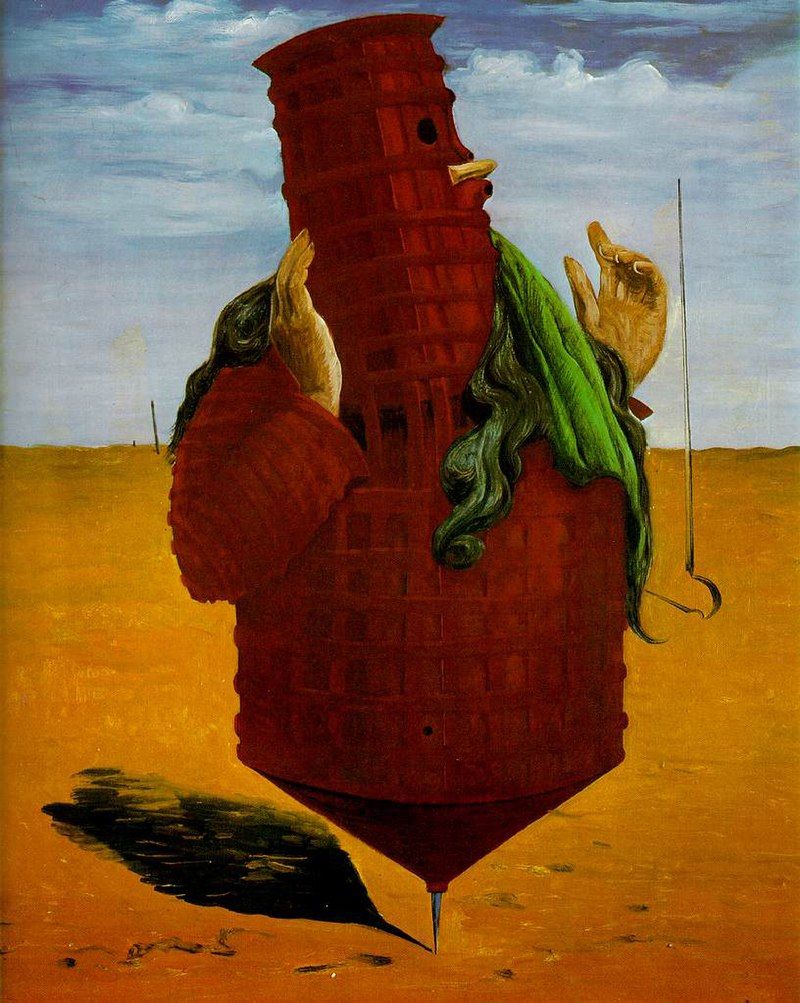

The expressionist art movement known as Dada had begun in Zurich during World War I, and became an international phenomenon. The basics of Dada, that you must know about, is it’s a rejection of logic, reason, and the aesthetics of capitalist society. Instead, Dada offers up irrationality, nonsense, and anti-bourgeois protests. In Germany, the Berlin group included members like Jean Arp, George Grosz and Hannah Höch. Jean Arp had showcased his work alongside Kandinsky and Matisse prior to WWI. Once involved with the Dada movement, Jean’s art became more enhanced. His work titled ‘Shirt Front and Fork’ created in 1922 shows Arp’s style of exaggerated and rounded, almost bulbous, silhouettes. Jean Arp and Max Ernst also formed a Cologne Dada group, and held a Dada Exhibition there that included a work by Ernst that had an ax "placed there for the convenience of anyone who wanted to attack the work". Max Ernst is, in my opinion, one of the quintessential Dada artists. His painting titled Ubu Imperator, created in 1923, depicts the character of Ubu, from a late 19th century French play, who is notorious for being infantile, stupid, gluttonous, and greedy. Except Ubu in this painting looks like a dark red patchwork dreidel, with a tiny fake mustache, large hands, and what looks like a wilted piece of lettuce hanging over his shoulders. Ubu Imperator represents the derision of authority and those in power. Worse than the emperor with no clothes, in Ernst’s opinion.

George Grosz’s artwork is satirical, using graffiti style to express the absurdity of the society he saw around him. His pen and ink drawings show corpulent businessmen, sex workers, criminals, and wounded soldiers. His style is deliberately crude, creating almost caricature drawings where you saw the heartbreak in the reality outside your door. Hannah Höch’s artwork is heavily based in photomontage. She is one of the only women famous within the artistic Dada circles. Many male artists provided lip service to including women to the movement, but Hannah is quoted as being the “sandwiches, beer, and coffee” of the Dada movement. Meaning her work was integral and fuel for others. Her 1919 work titled Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada through the Beer-Belly of the Weimar Republic is still considered an important piece of work to study, not just for its technical capabilities, but its political commentary, which was inherent to the Dada movement. It depicts the failed attempt at democracy of the Weimar Republic. It combines overlaid images of political leaders with sports stars, mechanized images of the city, and Dada artists.

Another art movement was New Objectivity, or Neue Sachlichkeit. The artists of this movement did not belong to a formal group. Various Weimar Republic artists were oriented towards the concepts associated with it, however. Broadly speaking, artists linked with New Objectivity include Käthe Kollwitz, Otto Dix, and George Grosz, who all "worked in different styles, but shared many themes: the horrors of war, social hypocrisy and moral decadence, the plight of the poor and the rise of Nazism". Otto Dix and George Grosz referred to their works as Verism, a reference to the Roman classical Verism approach called verus, meaning "truth", warts and all. While their art is recognizable as a bitter, cynical criticism of life in Weimar Germany, they were striving to portray a sense of realism that they saw missing from expressionist works. New Objectivity became a major undercurrent in all of the arts during the Weimar Republic.

Käthe Kollwitz’s work is in sculpture, etchings and woodwork, most famously seen in her works titled After The Battle and Mother with her Dead Son. After The Battle is part of a series of etchings called The Peasants War, which features a mother searching through corpses in the night, looking for the body of her son. Mother with her Dead Son is a sculpture, currently housed as a monument to the victims of war and tyranny, not quite in the Pieta style but similar. In a traditional Pieta style, the son rests on his mother’s knees. But in Kollwitz’s version, the son is crumpled on the ground between his mother’s legs. Embraced in his mother’s arms, he seems to be seeking her protection, rather than being a symbol of his mother’s grief.

Otto Dix’s works lingered on the subject of Lustmord, or sexualized murder. He drew your attention to the bleaker side of life, namely violence, old age, death, and prostitution. His triptych titled Metropolis, created in 1927-28, depicts three nighttime scenes from Weimar Germany. The middle panel shows the interior of a dance bar, with a dark red background, a brass band, a couple dancing intimately, and women dripping in jewelry and the latest fashions. The right panel shows a group of high-class prostitutes dressed in furs, who seem to be striding towards the viewer and carelessly walking past a war cripple. On the left panel, several prostitutes stand in front of the bar's red-lit entrance, looking at two men, one lying on the floor and the other another war cripple. The men are barked at by a dog. To say Dix was critical of Weimar society’s choice for oblivion after the horrors of WWI is an understatement.

At the beginning of the Weimar era, cinema meant silent films. Expressionist films featured plots exploring the dark side of human nature. They had elaborate expressionist design sets, and the style was nightmarish in atmosphere. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919), directed by Robert Wiene, is usually credited as the first German expressionist film. The sets depict distorted, warped-looking buildings in a German town, while the plot centers around a mysterious, magical cabinet that has a clear association with a casket. F. W. Murnau's vampire horror film Nosferatu was released in 1922. Fritz Lang's Dr. Mabuse the Gambler (1922) was described as "a sinister tale" that portrays "the corruption and social chaos so much in evidence in Berlin and more generally, according to Lang, in Weimar Germany". Futurism is another favorite expressionist theme, shown corrupted into a force of oppression in the dystopian film Metropolis (1927). The self-deluded lead characters in many expressionist films echo Goethe's Faust.

One of my favorite films from this era of cinema is M by Fritz Lang, made in 1931. It’s a mystery suspense thriller, involving the portrayal of Hans Beckert, a serial killer of children. The plot of the movie centers around the hunt for Hans by both police and the criminal underworld. The use of musical leitmotif is a practice still used today - the theme to ‘In the Hall of the Mountain King’ by Grieg is whistled by Hans as he hunts children only to murder them.The use of this melody throughout other scenes of the film, such as when the police are in pursuit of Hans, allowed the audience to know they were closing in on him. The criminals are the ones who ultimately nab Hans, and give him a kangaroo court trial. Hans pleads his case, saying that he cannot control his homicidal urges. He judges the other criminals for breaking the law by choice, and that they have no right to judge him. The police manage to find this “trial” taking place, and they arrest everyone, including Hans of course. At his “real trial”, the mothers of his victims weep in the gallery. The magic of this film is that it bridged the gap between silent movies and talkies. It’s a highly-rated movie for its lack of dialogue, the use of leitmotifs, and the clear-cut commentary on Lang’s hatred for what he saw as a grotesque society.

German expressionism was not the dominant type of popular film in Weimar Germany and was outnumbered by the production of costume dramas, often about folk legends, which were enormously popular with the public. Opulence, rather than the deliberation of postwar horrors, was what society desired. Why mope in the tragedy of death and destruction, when you could forget your worries at the cinema. However, the artistry of Weimar kept going.

The Blue Angel (1930), directed by Josef von Sternberg with the leads played by Marlene Dietrich and Emil Jannings, was filmed simultaneously in English and German. The film depicts the doomed romance between a Berlin professor and a cabaret dancer. Cinema in Weimar culture did not shy away from controversial topics, but dealt with them explicitly. Diary of a Lost Girl (1929) directed by Georg Wilhelm Pabst and starring Louise Brooks, deals with a young woman who is thrown out of her home after having an illegitimate child, and is then forced to become a prostitute to survive. This trend of dealing frankly with provocative material in cinema began immediately after the end of the War. In 1919, Richard Oswald directed and released two films that met with press controversy and action from police investigators and government censors. By the end of the decade, similar material met with little, if any opposition when it was released in Berlin theaters. William Dieterle's Sex in Chains (1928), and Pabst's Pandora's Box (1929) deal with homosexuality among men and women, respectively, and were not censored. Homosexuality was also present more tangentially in other films from the period.

Writers such as Alfred Döblin, Erich Maria Remarque and the brothers Heinrich and Thomas Mann presented a bleak look at the world and the failure of politics and society through literature. Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz is a mainstay still for scholars of German literature, published in 1929 with its panoramic portrayal of a modern metropolis. It's a marvel of literary modernism and is listed in the Top 100 Books of All Time by writers from around the world. Remarque wrote one of the most famous pieces of German literature of the modern age, All Quiet on the Western Front, published in 1928. This book inspired generations of military veterans to write about their experiences of war. The decadent cabaret scene of Berlin was documented by Britain's Christopher Isherwood, such as in his novel Goodbye to Berlin which was later adapted as the play I Am a Camera. Goodbye to Berlin was also the inspiration for a very famous musical called Cabaret. Thomas Mann’s 1924 masterpiece The Magic Mountain helped spur him to the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1929. This plot tells the tale of a very different Hans (than that of Fritz Lang’s movie M). This Hans is from a merchant family in Hamburg, and Hans is set to inherit a career in the shipbuilding family business. This is in the years leading up to WWI. Before settling into his new career, he decides to visit his cousin Joachim, who resides in the alpine town of Davos. Joachim is in Davos to seek a cure to his tuberculosis. Joachim’s sanatorium becomes a microcosm of pre-war Europe; with characters like Lodovico (an Italian humanist), Leo (a Jewish Jesuit in favor of communist totalitarianism), Mynheer (a dionysian Dutchman), and his love interest Madame Clawdia. Once at the sanatorium, Hans begins to show signs of a bronchial infection. His health continues to decline as he attempts to leave Davos and return to Hamburg. Hans ends up staying in Davos for seven years, only leaving as World War One breaks out to volunteer for the army. The text alludes to Hans’ demise on the battlefield.

Eastern religions such as Buddhism were becoming more accessible in Berlin during the era, as Indian and East Asian musicians, dancers, and even visiting monks came to Europe. Hermann Hesse embraced Eastern philosophies and spiritual themes in his novels. Specifically, Siddhartha, written in 1922, and Steppenwolf, published in 1927. Weimar Germany also saw the publication of some of the world's first openly gay literature. In 1920 Erwin von Busse published a collection of stories about sexually charged encounters between men and it was promptly censored. Its five stories depict a variety of sexually charged encounters between men, with characters that range from military school cadets and dance-hall regulars to a foreign businessman and a burglar. Though the Weimar Republic is celebrated for its "radical remaking of sexual norms", and its 1919 constitution prohibited censorship in principle, it also permitted statutes to regulate films, printed matter, and public presentations. For example, the film Different from the Others, which argued for the decriminalization of homosexuality, was released in May 1919 and banned nationwide in October 1920.

The theaters of Berlin and Frankfurt am Main were graced with drama by Ernst Toller and Bertolt Brecht. Many theater works were sympathetic towards Marxist themes, or were overt experiments in propaganda, such as the agitprop theater by Brecht and Weill. Agitprop theater is named through a combination of the words "agitation" and "propaganda". Its aim was to add elements of public protest (agitation) and persuasive politics (propaganda) to the theater, in the hope of creating a more activist audience. Among other works, Brecht and Kurt Weill collaborated on the musical or opera The Threepenny Opera (1928), which remains a popular reflection of the period. Toller was the leading German expressionist playwright of the era. He later became one of the leading proponents of New Objectivity in the theater. The avant-garde theater of Bertolt Brecht and Max Reinhardt in Berlin was the most advanced in Europe, being rivaled only by that of Paris. Bertolt Brecht was inspired by the works of cabaret performer and playwright Frank Wedekind. Wedekind wrote the play Spring Awakening before the onset of WWI, and yet its rejection of ‘Victorian norms’ and criticism of repressing human emotion is fuel to Brecht’s works. Like that of Mutter Courage, written in 1939 in a “white heat” over the course of one month, after the Nazis invaded Poland. The backdrop of the play is the Thirty Years War of the 1600s, but the criticism is about war profiteering, loss of human life for seemingly no reason, and the idea that virtues are not rewarded during corrupt times.

Lastly, the design field during the Weimar Republic witnessed some radical departures from styles that had come before it. Bauhaus-style designs are distinctive, and synonymous with modern design. Designers from these movements turned their energy towards a variety of objects, from furniture, to typography, to buildings. Dada's goal of critically rethinking design was similar to Bauhaus, but whereas the earlier Dada movement was an aesthetic approach, the Bauhaus was literally a school, an institution that combined a former school of industrial design with a school of arts and crafts. The founders intended to fuse the arts and crafts with the practical demands of industrial design, to create works reflecting the New Objectivity aesthetic in Weimar Germany. Walter Gropius, a founder of the Bauhaus school, stated "we want an architecture adapted to our world of machines, radios and fast cars." Berlin and other parts of Germany still have many surviving landmarks of the architectural style at the Bauhaus. Painter Paul Klee was a faculty member of Bauhaus. His lectures on modern art (now known as the Paul Klee Notebooks) at the Bauhaus have been compared for importance to Leonardo's Treatise on Painting and Newton's Principia Mathematica, constituting the Principia Aesthetica of a new era of art. Paul Klee’s works from the late 30s is what still sticks with us to this day, even if you’re not an art aficionado. His 1937 work titled Revolution des Viadukts shows the arches of a viaduct breaking loose from each other, refusing to be bound together in a chain and therefore rioting.

That was a lot of absurd, modern, and new for a time “between wars”. A lot of artists hoped their creativity and truth-telling could confront the massive failures they saw all around them. In their government, their economy, and the values of their society. Stay tuned for a brief look at what happened as the Weimar Republic fell.

A wide range of progressive social reforms were carried out during and after World War One. The Executive Council of the Workers' and Soldiers' Councils introduced the eight-hour work day, reinstated demobilized workers, released political prisoners, abolished press censorship, increased workers' old-age, sick and unemployment benefits and gave labor the unrestricted right to organize into unions. A series of progressive tax reforms were introduced including increases in taxes on capital and an increase in the highest income tax rate from 4% to 60%. The Youth Welfare Act of 1922 obliged all municipalities and states to set up youth offices in charge of child protection, and also codified a right to education for all children, while laws were passed to regulate rents and increase protection for tenants in 1922 and 1923. Housing construction was also greatly accelerated during the Weimar period, with over 2 million new homes constructed between 1924 and 1931 and a further 195,000 modernized. You could say the Weimar Republic was reaching for the ideal of what we would call a socialist state.

A republic like that is going to attract the political attention of conservatives and in Germany’s case, fascists. The elections of November 1932 yielded 33% to the Nazi political party, or the National Socialist German Workers Party for short. This was actually a decline from their previous July elections to Parliament. The Communist Party also did well in July. There was no majority party in Parliament in 1932 and there was infighting between President von Hindenburg, Chancellor von Papen, and Adolf Hitler, the leader of the party with the most votes - although not a majority. After November’s elections, and the Nazi party’s small decline, and other parties not maintaining a majority, it was thought that Hitler could be controlled if he was elected to the Chancellorship. On January 30, 1933 Hitler was sworn in as Chancellor. Within a couple weeks, parties in opposition to Hitler and the Nazis were considered the enemy. Members of other political parties were threatened, assaulted, and party meetings were banned in the Parliament building.

On February 27, 1933, the Reichstag AKA the Parliament building burned to the ground. A council communist named Marinus van der Lubbe was implicated, outright blamed, and subsequently tried and convicted of arson and treason. A 2019 discovery of an affidavit from that time frame, tells the tale of an SA officer (Nazi paramilitary) bringing van der Lubbe directly from an infirmary to the Reichstag, and he smelled smoke already. Thereby suggesting that the SA had something to do with setting the fire as a false flag attack. Hitler and the Nazi party used the burning of the Reichstag to blame the Communist Party and force President Hindenburg to invoke Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution, which “indefinitely suspended” protected civil liberties. This allowed the Nazis to swiftly round up, arrest, and summarily execute members of the Communist Party.

But it was the passing of the Enabling Act of 1933, which ultimately brought the Weimar Republic to an end. This act empowered the cabinet to legislate without the oversight or approval of the President or Parliament. The Act was formally titled the ‘Act for the Removal of Distress from People and Reich’. It negated the rights of habeas corpus, freedom of the press, freedom to assemble, privacy of the post, and enforced the legalization of search warrants without cause or evidence. In the months following the Enabling Act, all other political parties outside the NSDAP were banned and disbanded. Trade unions were dissolved. All media was brought under the control of the government’s propaganda office. When President Hindenburg died in 1934, the Hitler Cabinet passed the “Law Concerning the Head of State of the German Reich”, which passed presidential powers over to the chancellor: Adolf Hitler. The era of fascist dictatorship in Germany had officially begun.

The outcome most Weimar culturists feared through their artworks, publications, and philosophies had come to fruition. Many artists and creatives escaped to America, or remained in exile while Europe raged during the Second World War. Many returned home after the war and kept creating art; kept speaking truth to power. Only at that time, the world embraced it a little bit easier. Or at least, didn’t mock the absurdity of it all.

And that’s a walk on the wild side of German history, providing the answer to the trivia question: What important cultural movements existed in Germany between World War One and World War Two? I hope you’ve enjoyed this jaunt down Dada lane. Another episode of Not Trivial is coming soon, so please subscribe - available wherever you listen to podcasts. Thank you!