When and where did the Iron Age start?

We’ve all heard of the Iron Age. And some of us know that this age is characterized by the production of weaponry and tools through smelting and smithing. At least in Europe and the Ancient Near East. But did you know that ironworking was developed in sub-saharan Africa as many as 800 years before it developed in Ancient Greece?

Welcome to Not Trivial! A podcast that takes a deeper dive into the stories behind the trivia questions you might’ve heard at the pub. My name is Liz, and I’ve been a trivia nerd since I was young. My parents and I would play Trivial Pursuit often. Still do. I’ve hosted pub trivia, I’ve played pub trivia, and I’m a collector of random history, language, and world culture facts. One of my greatest passions is sharing what I’ve collected with others. I’m hopeful this podcast makes the trivia questions feel less trivial, and more important to understanding how the past creates the present, and subsequently the future. Let’s get started…

Today’s episode has to start by placing the Iron Age in the context of human history. We’re going way back - to the Stone Age. The Stone Age is a very broad prehistoric period, when tools with an edge or point were made of stone upon a strong surface, sometimes also stone. Think handheld axes, spearheads, arrowheads, etc. This age lasted quite a long time, roughly 3.5 million years, which means homo sapiens weren’t the only humanoids to understand how to make stone tools. Neanderthals also made and used stone tools. And the Stone Age, because it’s so long, is broken up into three phases: Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic. The Paleolithic is known for homo erectus, first use of fire to cook food, and the invention of harpoons. The Mesolithic is known for the beginnings of ceramic pottery and rock paintings. The Neolithic is known for the domestication of animals, introduction of farming techniques, and the use of tools like the sickle blade and larger axes. Tools like these helped humans plough the land and clear forested areas to build houses out of wood.

The Neolithic starts roughly 12,000 years ago and transitions to the Copper Age about 6,500 years ago. The Copper Age is the start of the Metal Ages, which goes onto the Bronze Age and then the Iron Age. In Europe, there are archaeological sites that show evidence of copper smelting at high temperatures. Like that of Belovode in Serbia. That site dates to roughly 5000 BCE. That’s right at the beginning of the Copper Age. Smelting is a big topic for today, so let’s understand what that means. Smelting is the process of applying heat to an ore, in order to extract a base metal. Ore is typically a chemical compound of the base metal amidst other chemical elements; and this is different from naturally occurring metals. A good example is gold versus silver. Gold occurs naturally in the environment and does not have additional chemical elements you need to reduce by smelting. Silver, on the other hand, can be mined, but is often found with high levels of lead and copper. Silver is actually often a by-product of lead or copper ore processing, rather than it being mined solely to extract silver.

Smelting is considered a fairly complex process, when thinking of human history. It requires an ability to melt metal ore, which to be fair is a different temperature depending on the ore. For example, zinc ore melts at roughly 420 degrees Celsius, or 790 degrees Fahrenheit. But nickel ore melts at roughly 1450 degrees Celsius, or 2650 degrees Fahrenheit. Copper ore is somewhere in the middle, melting at roughly 1100 degrees Celsius, or almost 2000 degrees Fahrenheit. But humans had learned how to use fire to cook food, which led to building kilns to fire pottery. This led to more ways to cook foods and also inventing new tools and weapons. And the method early humans used to smelt copper during the Copper Age varies. There’s the use of crucibles in Spain, but also evidence of the slagging process used in central Europe.

What is slag? Slag is the ferrous byproduct of extracting the base metal from ore. Which means it’s the excess, the unused stuff after you’ve extracted the copper or silver from the ore itself. Some of the earliest ores that were smelted were tin and lead. But these were not initially big influencers on civilization. Tin and lead can be smelted simply by placing the ore in a wood fire. Lead ore melts at roughly 325 degrees Celsius, or 620 degrees Fahrenheit. Lead is also very common, but it’s too soft for creating weapons or tools from. Eventually, humans figured out it was easy to cast and shape, which is where the first lead plumbing pipes came from in Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome.

Copper is not as easily smelted, especially with a melting temperature almost three times higher than that of lead. This is where the pottery kilns were likely put to use, it’s a theory. This is about the time when the Bronze Age starts though, around 3300 BCE, because copper combined with tin or arsenic produces the alloy of bronze. Bronze is significantly harder than copper, and was a strong influence on civilization as a whole. And when I say as a whole, I mean cultures around the world, sort of simultaneously but independent from each other, developed similar techniques to smelt bronze. Bronze was the peak of technology for a long time. It was made into swords, spearheads, battle axes, shields, helmets, knives, nails, cooking pots, jugs, cauldrons, and even horse harnesses. The Bronze Age is also when some cultures implement their first writing systems; like in Mesopotamia with cuneiform and Egypt with hieroglyphics. Clearly, the Bronze Age signifies a forward progression in human history.

But what about the Iron Age? When is the leap from bronze to iron? In the case of Ancient Greece, the Bronze Age ends rather abruptly and without a lot of explanation. This happened around 1150 BCE. It’s essentially what ushered in the Dark Ages of Ancient Greece. There are theories about how economic collapse alongside natural events, like droughts and volcanic eruptions and earthquakes, must have happened simultaneously. But economic collapse can be partially traced to metallurgy and the trade of precious ore. Or rather, lack thereof. The availability of tin is likely to have significantly decreased, causing bronze to become harder to make. And if cultures were meanwhile starting to engage in iron smelting and smithing, as iron was more readily available, then bronze would have been considerably devalued.

But as many other cultures around the world evolved from the Stone Age into the Copper Age and then into the Bronze Age, cultures in certain parts of Africa did not evolve the same way. Now we get to the good stuff! The earliest evidence of iron smelting is in Lejja, Nigeria. Slag blocks found there have been carbon-dated to around 2000 BCE. That’s a good 800+ years before the collapse of the Greek Bronze Age, which led to their Iron Age. And in this part of Africa, there is no found evidence of a transition phase between the Stone and Iron Age. There is a Bronze Age in eastern parts of Africa, like Egypt and what was once called Nubia. There is evidence of copper and bronze working sites in Niger dating from 1500 BCE, and yet no evidence of similar types of working sites in Nigeria, Cameroon, and the Central African Republic. Which is where the earliest iron working sites in the world have been located. This doesn’t necessarily mean West Africa did not use Bronze at all, it just didn’t happen on the same timeline as Ancient Greece or Egypt.

Remember though, that the evidence found dating so far back is slag blocks. This means smelting was occurring, since slag is a byproduct of the smelting process. The smelting process was done in what’s called a bloomery. A bloomery is a type of furnace that looks like a chimney sitting on the ground. Its heat-resistant walls are made from clay, earth, or sometimes stone. At the bottom of the bloomery are pipes or holes to allow air into the chimney stack. The process of smelting iron in a bloomery is not a simple process, definitely not as simple as smelting tin or lead in a wood fire. The melting temperature of iron ore is roughly 1550 degrees Celsius, or 2800 degrees Fahrenheit. That’s hotter than the melting temperature of nickel, and just shy of the melting temperature of titanium. Smelting iron in a bloomery is a complex process and it requires multiple people. It literally takes a village. But how did they smelt iron, which requires such a high level of heat, without having already smelted iron to build tools and machinery to then smelt more iron?

Let’s walk through the process sub-saharan Africans from 3500 years ago executed, in order to produce iron. First, you must prepare the ore; the ore has to be broken into smaller pieces. This means you’re swinging a heavy mallet or other blunt large instrument to try to break the ore. The same motion as chopping wood, but of course, much much harder. You must also have something to help the fire burn hotter. Initially, this would have been wood. Later uses of bloomeries would have used charcoal. The small broken bits of ore are placed in the bloomery through the top opening of the chimney. The ratio of ore to charcoal is one-to-one. The use of charcoal is ideal because the charcoal is almost pure carbon.

As charcoal burns, carbon monoxide is produced. And it's the carbon monoxide that helps reduce the amount of iron oxides in the ore. This means the ore isn’t actually melting, which means the temperature of the bloomery is concentrated, but not so high that the bloomery cracks or burns. It’s a low and slow process. Larger bits of ore are placed into the bloomery as the slagging process continues. Eventually, the hot liquid slag will run to the bottom of the furnace, effectively creating a bowl which will catch the iron particles. This new mixture of iron particles surrounded by slag is what’s called a bloom. It’s a spongy mass that is easy to forge, after first being wrought - or essentially, pounded again and again in both high heat and low heat, to slough off the slag.

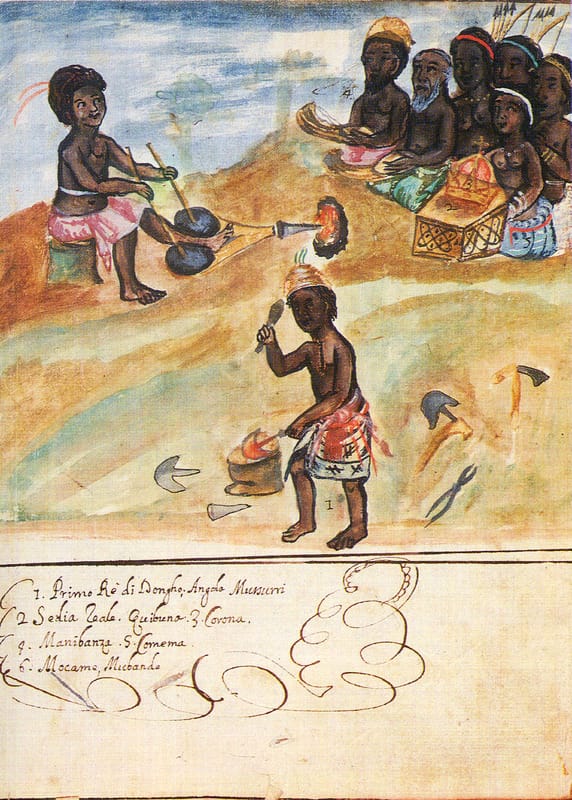

Now that we’re all experts on metallurgy… just kidding… There's a lot that can be done with wrought iron. Iron is far more durable than copper, although not as durable as bronze. But it is very easy to use in many ways. Farming tools, weapons, jewelry, pieces of art, and even instruments were made of iron in sub-saharan Africa. In West Africa, there was even currency made from iron. They were called kisi pennies, and they are essentially twisted iron rods ranging from 30 cm to 2 m in length. It’s possible kisi pennies were used as a simple trade currency, since iron rods could be melted down again and reshaped into whatever object was desired. This made iron very profitable. The smelting process was carried out away from the rest of a community, generally. Ironworkers engaged in rituals, like songs, prayers and dances, to ward off bad spirits and encourage a high yield of production for the community. Smelting was also linked culturally and socially to the fertility of a community. A successful production of iron would support the growth of the community, just as a thriving community can support a higher number of newborns. Bloomeries were sometimes even decorated to represent the female form, as the bloom was instrumental in creating the lifeblood of a community. Depending on the community and its culture, the ironworkers themselves had control of iron production. They were either seen as lower in society, since smelting and iron-working was seen as manual labor, or they were seen as witch doctors or of a supernatural status in the community, because of their deep knowledge of natural elements and their ability to bend nature to their will.

The Iron Age in Africa brought with it an expansion of agriculture, industry, trade, and political power. We can’t talk about the birth of iron smelting in Africa, without also talking about the powerful cultures that rose amidst the Iron Age. We’re going to start with the Nok culture of Nigeria. This civilization is credited with bringing iron metallurgy to West Africa. Nigeria, as we know it today, is a vibrant culture. It’s an economic leader on the continent of Africa, with over 230 million people living there today. Back in 1500 BCE, Nok culture inhabited the central parts of the current country’s geography, surrounding the area to the north of the current capital city of Abuja. The Nok people may have migrated from the central Sahara, traveling south to the riverbeds of the Niger and its subsidiaries. The Nok culture centered originally around pearl millet farming, and terracotta sculptures that have since been conserved in art museums like the Louvre.

The Nok culture settlements found so far have all been on top of or built into mountains. Which is intriguing, considering how much pearl millet remnants are found at archaeological sites. Millet can grow at altitudes, and needs a warm soil to grow well. So, a sub-saharan African savannah farmland makes sense. However, so far there’s been no evidence of millet farms actually found in Nok settlements. Just that pearl millet was used for feasting or ritual purposes perhaps. But stone grinding tools were found. Evidence of sharp or pointed stone or iron tools, like a spearhead or other projectile, has also not been found. It’s clearly an area where more study is required. This is difficult to do though, as many sites have been looted. We may never have a full picture of the Nok culture and its people. But we do know they smelted iron due to the slag evidence found in more than one ancient settlement site.

As much as we don’t know the Nok people, it’s theorized that their artistry and influence on other civilizations has been highly impactful. It’s entirely possible that the Nok were the predecessors of the Yoruba people. The terracotta sculptures of the Nok were so plentiful in number, they must have developed a system or means of production. The enlarged heads depicted in their sculptures have been thought to show respect for intelligence. As a funerary object, this signifies a cultural and possibly religious value that did continue on into the Yoruba tribe.

The Yoruba are a West African ethnic group living in modern-day Nigeria, Benin, and Togo. Approximately 52 million Yoruba people live in this region in Africa today. The center of the Yoruba people thousands of years ago, however, was the city of Ile-Ife. This ancient city in southwest Nigeria has existed since roughly the 6th century BCE, possibly older than that. Its origins, as the tale goes, center around two divine brothers: Obatala and Oduduwa. Obatala was tasked by his father, the Supreme God, to create earth, but he somehow found some palm wine and was too intoxicated to finish the task. His younger brother Oduduwa created Earth instead, and founded the city of Ile Ife and started a divine royal dynasty for the Yoruba people. Obatala, once unintoxicated, helped his brother create the first Yoruba people out of clay. Ile Ife stands for “Home of Expansion”.

This story is important, because the Yoruba culture did go through a Bronze Age. As I said before, just not at the same time as the rest of the world. The bronze metalwork and sculptures of Ife are magnificent. The most magnificent of the sculptures are the bronze heads of Ife, depicting a naturalistic and sophisticated crowned figure. If Obatala created the first Yoruba people out of clay, the artists of Ile Ife created realistic royal heads out of bronze as a mark of intelligence, talent, and loyalty. The most famous sculpture is three-quarters life size, and is indicative of either an individual artist or specific artist’s workshop. Colonialist opinions were heavily skewed towards devaluing African art, but if we want to play the comparison game, the cast bronzes of Europe at a similar time were stylistically completely different, but equally as difficult to create.

The bronze heads of Ife are stunning, and they only date to the 14th century CE. But what we know about art is that it’s not suddenly created overnight. Techniques develop over the course of generations. Masters of metalworking learned from their forefathers, and they learned from their forefathers. The fact the bronze heads of Ife look like they do is a testament to the cultural significance of metalworking in West Africa. That, and they’ve also found scientific evidence of metal working culture dating to the 9th century CE. It is now recognized that these statues represent an indigenous African tradition that attained a high level of realism and refinement.

Another culture that excelled at metalworking was the Kingdom of Benin. Let’s clear things up about the use of the name Benin. Because the country of Benin today has no historical relation to the Kingdom of Benin from the 9th to 16th century CE.The country of Benin we know today was previously known as Dahomey from the 17th century until about 1975. Dahomey is the basis for the modern film ‘Woman King’ starring Viola Davis. And that’s a whole different episode… No, the Kingdom of Benin is much older. It is one of the oldest and most developed states along the coastal region of what we now call West Africa. Iron working was a strong foundation of the kingdom, as was agriculture, ivory trading, and forestry for the sake of building homes and defenses. Excavations in Benin City have shown extensive wall building, moats, fortified gateways, and wide avenues for markets and social life. This was a bustling region.

The Benin Bronzes are world-renowned. It’s a group of several thousand plaques and sculptures that decorated the royal palace. These bronzes tell the history of the people and the kingdom. They called themselves Edo. The cultural significance of having bronze plaques and sculptures of heads is very similar to that of Ile Ife. It is thought the two cultures influenced each other heavily. The Benin Bronzes have surfaces that only highlight the contrast between the metal and light. They depicted warriors or nobles, often together inside the palace. When the Edo started trading with the Portuguese, they depicted what the Portuguese traded, and how the European traders dressed. The plaques are all only about ⅛ inch thick, which sounds very thin, but for metalworking it’s not. The Statue of Liberty is the same thickness, which for a very large sculpture requires a lot of support bars. But for bronze plaques, ⅛ inch thickness is about right for smaller scales, and is actually quite thick.

The Benin Bronzes are actually masterpieces of what’s called lost-wax casting. This is the method the Edo became experts in. The process consists of multiple steps. Let’s pretend we’re making a bronze cast of an apple. First, we create an original model of an apple from clay or wax. It’s a full blown apple, just not made of metal yet. Then, we create a mould of the apple model. So, we use a substance like plaster - or in more modern times, fiberglass or silicone. Since the apple is round, it means we likely have two sides of the mould that fit together around the model. We might also need multiple moulds, since there’s not just the apple itself, but the stem sticking out of the top. We don’t want that to break off, so we create a mould of just that part of the model. Now that we have a few hollow moulds, we pour molten wax into them and ensure that wax is evenly covering all inner surfaces of the mould. And we might want a really thick layer, so we pour molten wax in multiple times to get the desired thickness. Once the wax is hard and set, we then carefully remove that wax from the mould. So now instead of a full-bodied clay model, we have parts of a hollow model in wax. Like a copy of the original model that we then fit together to look like a whole apple. These are wax castings. The wax casting is then ‘chased’, which means its lines or wrinkles are ironed out, and then ‘sprued’, which means the casting is surrounded by a fire-proof mould that will have passages for a molten substance to enter. It’s usually a vertical passage. The fire-proof grit or slurry is also poured into the inside of the wax casting.

So, now we have an inner and outer layer of a fire-proof substance and the wax casting between the two. We then bake this in a kiln upside down. The bottom of this fire-proof mould will often have the opening of the vertical passage. As the kiln heats up, the wax will begin to melt out. This should mean that any passages we will use to pour the bronze are empty. We remove the fire-proof mould from the kiln to let it cool, now free of wax. After it cools, we should be able to pour water into the mould openings to test for leaks or cracks. We then place our mould back in the kiln, if we’ve patched any cracks or leaks. We remove the mould from the kiln and quickly bury it in sand, which preserves the heat of the mould from the hot kiln. With only the opening of the passage for pouring the bronze accessible at the top, we take our molten bronze and pour it in, and it will take up the space where the wax was previously. The moulds are allowed to cool and removed from the sand. The shell of the fire-proof mould is hammered away, the bits of the sprue or passageways are cut away, and just as the wax copy was chased, the metal is also.

If me explaining that process to you felt arduous, imagine what West African metal workers spent their precious time and energy doing. Before the Industrial Revolution. It really sheds light on how intrinsic and deeply important artistry is to representing a culture and helping an empire to thrive. This was the very worthy deep dive behind the trivia question: When and where did the Iron Age start? Clearly, it’s not all about Europe! Stay tuned for a brief update on Africa’s mineral riches of today.

We’ve learned today that West Africa, specifically Nigeria, has been integral to developing metal working and the art that stems from mining and processing ore. Modern-day African countries are still at the forefront of this industry. The second-largest mineral industry in the world is Africa’s. Mineral exploration and production makes up a significant part of some African countries’ economic growth. The African continent is very richly endowed with minerals like bauxite, cobalt, industrial diamond, phosphate rock, and zirconium. To name a few.

Almost twenty years ago, 73% of the world’s diamonds came from African countries like Botswana, the DRC, South Africa, and Angola. 89% of the world’s gold came from African countries like South Africa, Ghana, Tanzania, and Mali. 16% of the world’s uranium came from Namibia, Niger, and South Africa. And a whopping 92% of the world’s platinum came from South Africa. To say that some African countries are highly and dangerously dependent on mineral production and export is a vast understatement.

Some of the more vital minerals and metal ore are found in countries like Guinea, Zambia and Mauritania. These are minerals like bauxite, which is used to create the handy aluminum foil we use in our kitchens every day. Guinea is a world leader in bauxite production. The country has over 100 companies associated with aluminum and over two dozen of them are internationally owned or operated. Guinea’s bauxite reserve is over 7 billion metric tons, which is a quarter of global reserves of bauxite. As a country, where over 12 million people live, only a few tens of thousand of jobs are accessible for Guineans in the mining industry. And the average wage is less than a dollar a day. Guinea also has 4 billion metric tons of iron-ore reserves and expects to continue mining for gold and diamonds as well.

Zambia by contrast, has largely based its economy on the copper mining industry. The Mufulira mine in the Copperbelt district of Zambia was built in the 1930s and a large town has sprung up around it to house its workers, and tangentially the services they need to survive. Copper production for Zambia was at its peak in the late 60s and early 70s. Mines like Mufulira were bustling and the Copperbelt enabled Zambia to provide an economy for the fledgling independent country, as of 1962. However, the wealth of the mines also gave political adversaries and guerilla militias something to aim for, as they destabilized the country.

Mauritania is not a wealthy country by any means, and its exports are squarely centered around minerals and agriculture. Nearly 50% of the country’s exports are attributed to iron ore exports. Yes, we’re back into iron! There are new gold and copper mines being built still with some investment. But the country’s GDP is very low when viewed per capita. It is increasing, but a disappointing $2100 US dollars per person. When compared with other mineral-producing countries in Africa, it’s relatively small. With a population of around 4.5 million, that’s a total GDP of just under 10 billion dollars. Guinea has a GDP of 16 billion, and Zambia has a GDP of 22 billion.

But the big producer on the continent is South Africa. And not only big as in volume, but big as in variety. It has a history of being a big mining producer. For nearly a century, it was the world leader in gold production. It is currently the world’s leading producer of chrome, manganese, platinum, vanadium, and vermiculite. It is the second-largest producer of ilmenite, palladium, rutile, and zirconium. It is also the world’s third-largest coal exporter. South Africa recently overtook India as China’s third-biggest supplier of iron ore.

Africa as a continent is still being pillaged by foreigners. The average mine employee is faced with a high chance of experiencing a fatal or near-fatal accident, violence from the mining company’s security, and of course the environmental factors: high temperatures, long distances traveled underground, and inhaling dust compounded with silica or worse. High rates of tuberculosis and silicosis occur, meaning the lifespan of an African miner is shortened by a significant amount of years. The average lifespan of a male from the Democratic Republic of Congo or Guinea is less than 60 years. Mauritania, South Africa, and Mozambique are only slightly better than that at less than 65 years.

The mining market in Africa is expected to reach a value of $800 billion by the year 2030. These are critical sources of revenue for many African countries, the mines. Mining has always occurred in Africa, but to what benefit. How will some African countries survive if their natural resources run out, or are devalued in the markets, or the earth they so rely on begins to decay due to the impact of the industry? I hope you’ve enjoyed this insight into a history of Africa not widely known! Another episode of Not Trivial is coming soon. Please subscribe and listen to the show wherever you find podcasts. Thank you!